Get Comfortable with Logistic Regression and What It Can Tell You

I want to have something on my blog for students in my advanced quantitative methods class to read to better acclimate themselves to the logistic regression model. This is a curious thing, given everything else on my blog. I use the logistic regression a lot in assorted R tutorials I publish, including how to read a regression table and how to do model simulation. However, I’ve never really belabored the model itself in any detail. The closest I’ve done is a tutorial I wrote for a methods class I taught in 2020. There’s more I’ve learned along the way about how to convey information about the logistic regression, and want to do that here.

I will eschew a lot of the hand-wringing about the “linear probability model” in this post, and I may revisit this post at sometime later to discuss the logistic distribution. You should be able to follow along if you read my previous post on the probit model, which does cover a lot of these bases as to the curve-fitting inherent to this model (and the probit equivalent). You may also benefit from reading about the Poisson model, which likewise has a log transformation (and risk/rate ratio) baked into the quantity it returns. Logarithmic transformations have interesting properties that are useful to review. While it’s not my post, I do rather like this tutorial from Robert Kubinec that also explains the theoretical intuition behind the logistic regression. Calling the “linear probability model” advocates as “flat Earthers” is a nice cherry on top. For this tutorial, I’ll assume you’ve read this and know you have a model you want to unpack in greater detail for a dependent variable that is binary.

Here are the R packages that will be making an appearance.

library(tidyverse) # for most things

library(stevedata) # for the data

library(stevemisc) # for some helper functions, prominently binred_plot()

library(stevethemes) # for plotting element

library(performance) # for some pseudo-R-squareds.

Here’s a table of contents.

- Briefly, the Intuition

- The Data, and the Context

- Specifying the Model and Intepreting its Immediate Output

- Getting Specific with the Model’s Immediate Output

- Logistic Regression Diagnostics/Fit Assessments

- Conclusion

Cool, let’s get going.

Briefly, the Intuition

The intuition behind the logistic regression comes from the same issue described in my post about the probit model and reading Cramer (2004) will likewise be informative. Namely, there is a linear probability we want to describe about a phenomenon that is functionally non-linear. Assume the following deterministic, linear relationship.

\[y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x\]What makes this relationship linear when the outcome (\(y\)) is discrete? What unbounded relationship on the right-hand side of the equation describes a fundamentally bounded phenomenon on the left-hand side of the equation? A binary \(y\) we want to model is maximally discrete. It’s observed or it isn’t. Under these circumstances, modeling the underlying probability by which \(y\) is 1 is what interests us. Probability by way of the binomial distribution gets us out 0-1 land, but it too has some discrete properties. It can be more granular than 0 or 1, but it can’t be less than 0 or more than 1. Thus, something needs to constrain this linear predictor on the right-hand side of the equation to respect this. It’s why you’ll often see GLMs stylized as formula with an eta wrapper, like this.

\[\eta(x) =\beta_0 + \beta_1x\]What function does this, especially when we’re interested in probability? Here’s where some knowledge of probability and odds goes a long way. Probability is the chance of some event happening and is bound between 0 and 1. Odds are relative probabilities, defined as the probability of some event happening divided over the probability the event doesn’t happen. The odds give us one out because they are unbounded on the right. If the probability of an event happening is an absolute metaphysical certitude that it will happen, then the odds are infinity (i.e. 1/(1-1) = \(\infty\)). However, they retain a left bound at 0. When the probability of an event happening is an absolute metaphysical certitude that it won’t happen, the odds are 0 (i.e. 0/(1-0) = 0). Enter the natural logarithm to save the day. Log-transformed odds—“logits”, for shorthand—are completely unbounded. The log of 0 is negative infinity and the log of infinity is still infinity. Thus, the link function for this generalized linear model is stylized as follows.

\[\eta(x) = log(\frac{p}{1-p}) = \beta_0 + \beta_1x\]There’s more to add here, certainly about maximum likelihood estimation, but that’s the long and short of it to get started. We have a discrete dependent variable that is observed as 1 or 0. We have an underlying phenomenon (probability) that governs whether the outcome is observed or isn’t. That phenomenon has fundamental bounds we must respect, but we want the linear relationship to be monotonic and unbounded. That’s basically what’s happening here.

The Data, and the Context

The data I’ll be using should be familiar to those who learned applied statistics by way of John Fox. This is a survey data set from Chile about an upcoming plebiscite concerning the future of Augusto Pinochet’s regime in 1988. I ported these to {stevedata} as chile88 and did some cosmetic edits to make it a little distinguishable from what is available in the {cardata} that supports his textbook.

Unfortunately, there is not a lot of information about this data set that is independent of its intended use, but the data are purportedly from a national survey carried out by FLACSO in Chile in April and May 1988 about an upcoming October plebiscite to continue or end Augusto Pinochet’s regime. The plebiscite itself was the byproduct of an eight-year sunset period that Pinochet announced in 1980 in its new constitution. The plebiscite, as it was written in the document, would allow voters to vote “yes” to continue Pinochet’s rule for another eight years or “no” to reject the candidate. If “no” carried, Pinochet would continue as executive and the military would continue as legislative body for another year and a half until elections held afterward would replace them in March 1990. That is quite the lame duck period.

No matter, respondents could declare that they intended to vote “Yes” (“Y” to continue Pinochet’s regime), “No” (“N”, to end Pinochet’s regime), or could declare they were going to abstain (“A”) or were undecided (“U”). The data that are available offer some information about the region (region) of Chile in which the respondent lives, the population size of their community (pop), whether the respondent self-identifies as a woman (sex), the respondent’s age (age), educational attainment (educ), monthly income in pesos (income), and some scale about how much respondent’s support the status quo (sq). We’ll pursue a simple model in which we will focus on just those that will vote “Yes” to “No”, subsetting out the abstentions and undecideds from the analysis.1 We’ll model intended vote as a function of the respondent’s age, monthly income (logged), whether the respondent is a woman, and whether the respondent has a post-secondary education.2 We’ll prepare the data for analysis.

chile88 %>%

mutate(votedum = case_when(vote == "Y" ~ 1,

vote == "N" ~ 0),

ps = ifelse(educ == "PS", 1, 0),

ln_income = log(income)) -> Data

Data

#> # A tibble: 2,700 × 11

#> region pop sex age educ income sq vote votedum ps ln_income

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 N 175000 0 65 P 35000 1.01 Y 1 0 10.5

#> 2 N 175000 0 29 PS 7500 -1.30 N 0 1 8.92

#> 3 N 175000 1 38 P 15000 1.23 Y 1 0 9.62

#> 4 N 175000 1 49 P 35000 -1.03 N 0 0 10.5

#> 5 N 175000 1 23 S 35000 -1.10 N 0 0 10.5

#> 6 N 175000 1 28 P 7500 -1.05 N 0 0 8.92

#> 7 N 175000 0 26 PS 35000 -0.786 N 0 1 10.5

#> 8 N 175000 1 24 S 15000 -1.11 N 0 0 9.62

#> 9 N 175000 1 41 P 15000 -1.01 U NA 0 9.62

#> 10 N 175000 0 41 P 15000 -1.30 N 0 0 9.62

#> # ℹ 2,690 more rows

Specifying the Model and Intepreting its Immediate Output

The simple generalized linear model with the logit link has a simple function in R, especially if you’re accustomed to the lm() function. Instead of lm(), it’s glm(). There’s an optional family = binomial(link = 'logit') argument you’ll need to specify in the function to return what you want.

M1 <- glm(votedum ~ age + sex + ps + ln_income,

Data, family=binomial(link='logit'))

summary(M1)

#>

#> Call:

#> glm(formula = votedum ~ age + sex + ps + ln_income, family = binomial(link = "logit"),

#> data = Data)

#>

#> Deviance Residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -1.6204 -1.1111 -0.7588 1.1241 1.6924

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) -1.506192 0.543630 -2.771 0.0056 **

#> age 0.018210 0.003396 5.363 8.19e-08 ***

#> sex 0.575030 0.100186 5.740 9.49e-09 ***

#> ps -0.631244 0.140144 -4.504 6.66e-06 ***

#> ln_income 0.062679 0.053210 1.178 0.2388

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

#>

#> Null deviance: 2361.7 on 1703 degrees of freedom

#> Residual deviance: 2269.9 on 1699 degrees of freedom

#> (996 observations deleted due to missingness)

#> AIC: 2279.9

#>

#> Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4

I encourage students who are completely unfamiliar with assorted link functions to go “stargazing” to make sense of the important results. All my guides for interpreting regression analyses say to do this, including the very first one I wrote over 10 years ago(!). Step 1: find the coefficients you care about. Step 2: assess whether they are positive or negative. Step 3: assess whether they are “statistically significant” (i.e. can be distinguished from a null hypothesis of no relationship).

In our case, the model tells a fairly straightforward story. Adjusting for everything else in the model, older respondents are more likely to say that they will vote to continue the Pinochet regime and that effect of higher levels of age is “statistically significant”. Adjusting for everything else in the model, having a post-secondary education decreases the likelihood the respondent would vote to continue the Pinochet regime. Adjusting for the basic demographics, there is no discernible effect of higher levels of logged monthly income on the vote in the upcoming plebiscite. Just about the only thing that is mildly surprising is that women are more likely than men to support the continuation of the Pinochet regime in the upcoming plebiscite. Context clues go a long way toward understanding the age and education variables, though I expected there to be a null effect for gender differences.3

Getting Specific with the Model’s Immediate Output

There are several ways you can make sense of the model’s immediate output on its own terms, and I’ll discuss these in turn.

Interpreting the Logit on its Own Terms

My guide on making sense of the probit model encourages the researcher to come armed with basic information about the dependent variable being modeled. The same thing applies here as the probit model and the logistic regression are doing basically the same thing: modeling transformed probabilities that an outcome is 1 versus 0. It’s just a different link function.

p_y1 <- mean(Data$votedum, na.rm=T) # what is the proportion of 1s to 0s?

p_y1 # let me see it...

#> [1] 0.4940239

base_odds <- p_y1/(1 - p_y1) # let me made that an odds

base_odds

#> [1] 0.976378

log(base_odds) # let me log-transform that to a "logit" (i.e. a natural-logged odd)

#> [1] -0.02390552

qlogis(mean(Data$votedum, na.rm=T)) # let me do the above, but in fewer steps

#> [1] -0.02390552

plogis(qlogis(mean(Data$votedum, na.rm=T))) # let me get my p_y1 back

#> [1] 0.4940239

# neato torpedo!

In the data we’re modeling, about 49% of respondents would vote to continue the Pinochet regime. Alternatively: the probability that the votedum variable is 1 versus 0 for those saying their mind is made up one way or the other is 0.4940239 The natural logged odds, all else equal, that coincides with that probability is -0.0239055. Let’s go back to our regression summary above and observe the statistically significant effect of that education variable. We would interpret that coefficient as saying the following:

Adjusting (“controlling”) for everything else in the model, the effect of having a post-secondary education versus not having a post-secondary education would decrease the natural logged odds of voting to continue the Pinochet regime by .631244 (and that effect is statistically discernible from zero).

If you wanted to make sense of that information, here’s how you could do it.

The model’s output suggests that if a respondent were at the sample average in their probability of voting to continue the regime, and that respondent did not have a post-secondary education, the probability of voting to continue the Pinochet regime would change from .494 to .341 for having a post-secondary education.

plogis(qlogis(mean(Data$votedum, na.rm=T)))

#> [1] 0.4940239

plogis(qlogis(mean(Data$votedum, na.rm=T)) + as.vector(coef(M1)[4]))

#> [1] 0.34183

# The change in probability

(plogis(qlogis(mean(Data$votedum, na.rm=T)) + as.vector(coef(M1)[4])) - plogis(qlogis(mean(Data$votedum, na.rm=T))))

#> [1] -0.1521939

The “Divide by 4” Rule

I talk about this parlor trick a lot because it’s one of my absolute favorites in all of applied statistics. To the best of my knowledge, we have Gelman and Hill (2006, 82) to thank for this. Briefly, and at the risk of plagiarizing myself any further from past tutorials, the logistic curve (the familiar “S” curve) is steepest in the middle, which is at 0. That means the slope of the curve (i.e. the derivative of the logistic function) is maximized at the point where Be^0/(1 + e^0)^2. Whereas we remember that e^0 = 1, that means that resolves to B/4. This tells us that the regression coefficient, divided by 4, is the estimated maximum difference in the probability that y is 1 for a one-unit change in the variable of interest.

As a shorthand, this is fantastic and performs really well when the probability that the outcome variable is 1 is near .5. That’s fortunately the case we have here. Observe how close the “divide by 4” rule performs compared to a manual calculation in the change in probability from the baseline probability derived from the overall sample.

broom::tidy(M1) %>%

mutate(db4 = estimate/4,

manual = plogis(qlogis(p_y1) + estimate) - plogis(qlogis(p_y1))) %>%

select(term, estimate, db4, manual) %>%

slice(-1) %>% # "divide by 4" is inapplicable to the intercept, so let's not look at it.

data.frame

#> term estimate db4 manual

#> 1 age 0.01821009 0.004552523 0.004552242

#> 2 sex 0.57503003 0.143757507 0.140372542

#> 3 ps -0.63124435 -0.157811087 -0.152193938

#> 4 ln_income 0.06267878 0.015669694 0.015668196

While I encourage students to not stop here in terms of unpacking logistic regression coefficients, I do think it’s an excellent place to start. It’s also about where I start in terms of evaluating logistic regression coefficients after I’ve assessed sign and significance.

The Odds Ratio

When I was in graduate school learning about statistical models, practitioners in my field that I followed never seemed comfortable with the logistic regression coefficient but did seem comfortable with the odds ratio. Then and now, I’m in the opposite camp. I’ve always felt odds ratios were weird ways of summarizing the logistic regression but the logit on its original scale always made sense to me. This is largely because odds ratios are left bound at 0 and serve as a kind of intermediate step from converting a probability to a logit. If you’re arguing for a negative relationship, you’re looking for an odds ratio that’s less than 1 and has a confidence interval that does not include 1. I’m more inclined to look for a negative or positive coefficient for the same information. Different strokes, I ‘spose.

The logic here is similar to the “rate” ratio from the Poisson model. If you understand what that’s doing in the Poisson context, you’ll understand what it means in this context. Both have logarithmic transformations. Exponentiating them “undoes” the logarithm and returns a ratio of interest to communicate the expected change. However, calculating them is multiplicative and not additive.

# First, let's add some odds ratios to our summary output.

broom::tidy(M1) %>%

mutate(db4 = estimate/4,

manual = plogis(qlogis(p_y1) + estimate) - plogis(qlogis(p_y1))) %>%

bind_cols(., as_tibble(exp(cbind(coef(M1), confint(M1)))) %>% rename(or = V1)) %>%

select(term, estimate, db4:ncol(.)) %>%

slice(-1) # don't look at the intercept

#> # A tibble: 4 × 7

#> term estimate db4 manual or `2.5 %` `97.5 %`

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 age 0.0182 0.00455 0.00455 1.02 1.01 1.03

#> 2 sex 0.575 0.144 0.140 1.78 1.46 2.16

#> 3 ps -0.631 -0.158 -0.152 0.532 0.403 0.699

#> 4 ln_income 0.0627 0.0157 0.0157 1.06 0.959 1.18

# Let's focus on the education variable for illustration's sake

base_odds # Here's our baseline odds

#> [1] 0.976378

as.vector(coef(M1)[4]) # our coefficient of interest

#> [1] -0.6312443

as.vector(exp(coef(M1))[4]) # our coefficient of interest, exponentiated as an odds ratio

#> [1] 0.5319295

new_odds <- base_odds*as.vector(exp(coef(M1))[4]) # new odds = multiplicative change when "un-logged"

new_odds # our new odds

#> [1] 0.5193642

base_odds/(1 + base_odds) # baseline odds, as probability

#> [1] 0.4940239

new_odds/(1 + new_odds) # new odds, as probability

#> [1] 0.34183

# change in probability, same as above

(new_odds/(1 + new_odds)) - base_odds/(1 + base_odds)

#> [1] -0.1521939

You could do it this way, though I’ll reiterate I’ve always thought this approach to summarizing a logistic regression was weird and not very intuitive.

Logistic Regression Diagnostics/Fit Assessments

Generalized linear models don’t have some of the simpler diagnostics that the linear model has, though there are some corollaries we can discuss. There’s more I can add later about predictive accuracy, and may come back to that at another point.

“R-Squared”

R-squared is a convenient way of assessing how well a linear model’s inputs fit the output. Bound between 0 and 1, higher values indicate a better fit for the data on fairly simple terms. For example, a linear model R-squared of .43 suggests 43% of the variation in the outcome variable is explained by whatever the inputs are in the model. However, such a simple metric has no one-to-one equivalent in the generalized world. There are, however, some “pseudo” R-squareds for generalized linear models that can be used to communicate the same basic information. I’m agnostic on whichever is the “best” one as all provide at least some information about how much variation is explained in the model. I’ll just discuss the two I know the best.

For one, McFadden’s R-squared will divide the log likelihood of the model over the log likelihood of the null model that includes just an intercept. Subtract 1 from that quantity and you’ll get McFadden’s R-squared. The information it communicates works much the same way as the simple R-squared in the linear model context. Values closer to 0 suggest the fitted model is not that different from the null model. Values closer to 1 suggest near perfect fit to the data. There’s also an “adjusted” variant that works in the same basic way as the adjusted R-squared of the linear model. There’s a downweight applied to the log likelihood of the full model equal to the number of estimated parameters in the model.

M0 <- glm(votedum ~ 1,

Data, family=binomial(link='logit'))

1-((M1$deviance)/(M0$deviance)) # technically should be logLik, but deviance works

#> [1] 0.06797375

# if you're curious, deviance(M1)/2 = logLik(M1)

# in the {performance} package...

r2_mcfadden(M1)$R2

#> McFadden's R2

#> 0.06797375

McFadden’s R-squared has been around for like 50 years and is kind of the “default” of the R-squared corollaries for the logistic regression model. The other R-squared I find kind of intriguing is fairly recent by comparison. Tjur (2009) proposes another one that is much simpler by comparison, and also kind of fun to consider. Take the fitted values from the model and convert them from the logit to the predicted probability. Calculate the mean predicted probability for the 1s and the 0s and take the absolute value of that difference. Ideally, a model that fits the data really well will be nailing the 0s and the 1s, increasing the difference in predicted probabilities (but still capping them at 1). A model that doesn’t fit the data well at all will be struggling to predict anything, resulting in predicted probabilities for the 1s and 0s that aren’t that different from each other (converging on 0). It’s beautifully simple.

broom::augment(M1) %>%

select(votedum, .fitted) %>%

mutate(p = plogis(.fitted)) %>%

summarize(mean = mean(p), .by=votedum) %>%

mutate(diff = abs(mean - lag(mean))) %>% data.frame

#> votedum mean diff

#> 1 1 0.5181456 NA

#> 2 0 0.4651812 0.05296444

# in the {performance} package...

r2_tjur(M1)

#> Tjur's R2

#> 0.05296444

There are more pseudo-R-squareds I invite you to read about at your own leisure. All will largely be telling you the simple model we have doesn’t offer a great fit to the data.

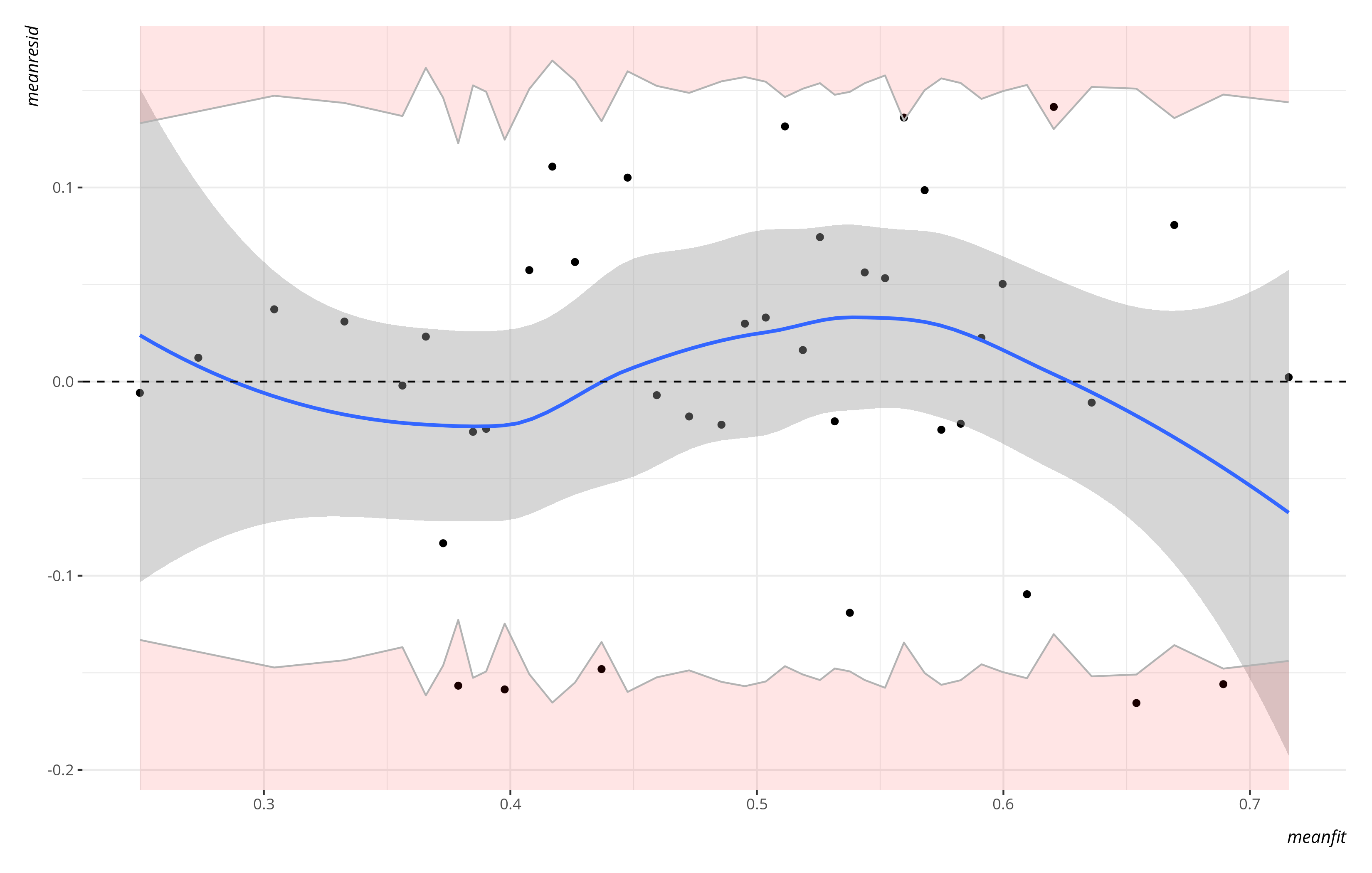

The Binned Residual Plot

When I teach students about the linear model, I emphasize the fitted-residual plot is the most “bang for your buck” linear model diagnostic. You can issues concerns of linearity, additivity, and homo-/heteroskedasticity from just one plot. Unfortunately, there is no perfect equivalent for logistic regression, but there is one that approximates some of the same basic information. It’s the binned residual plot.

My inspiration for teaching this diagnostic comes from Gelman and Hill (2006, 96), who freely confess that what’s returned is somewhat arbitrary and a function of how many bins you want. They propose, and I implement below, a rule of thumb for “binning” the fitted values of the model into particular groups. For larger data sets (n >= 100, which we have here), the number of bins are the rounded down (“floored”) square root of number of observations in the model. We have 1,704 observations in the model and the square root of that floors to 41. These 41 bins will span the range of the fitted values, for which we’ll calculate the mean of the fitted values in the bin. For the residuals of those observations in each bin, we’ll calculate a 95% interval and hope that the residuals are in bounds. When plotted with my binred_plot() function in {stevemisc}, they’ll look something like this.

binred_plot(M1) + theme_steve()

The dots coincide with the coordinates of the mean fitted values for a particular bin of observations, along with their mean residuals. The band you see coincides with 95% intervals. A LOESS smoother will look for illustrative evidence of non-linearity as well, but the real important information comes in identifying what percentage of observations come out of bounds. If you use this function of mine in R, you get the following console output alongside the plot. I’ll reproduce it below.

34 of 41 bins are inside the error bounds. That is approximately 82.93%. An ideal rate is 95%. An acceptable rate is 80%. Any lower than that typically indicates a questionable model fit. Inspect the returned plot for more.

What you do with this information is up to you, but severe violations of this suggest something should be log-transformed or something should be interacted because of pockets in the data. In an older version of this same basic tutorial, it was very clearly the case there are people who had all the telltale signs of a Trump voter (but didn’t vote for him) and people who had all the telltale signs of a Clinton voter (who didn’t vote for her). The plot here, by comparison, doesn’t look so bad? Either way, I’m not sure what else we could do with it based on the limited information available to us.

Conclusion

There really isn’t much to conclude, at least I don’t think. Don’t be a flat Earther.

-

I won’t look into this any further for the sake of this post, but there is good reason to believe a good chunk of the self-declared abstentions are actually people who want to end Pinochet’s regime but do not feel comfortable saying as much. Compare the support for the status quo variable by intended vote pattern to see for yourself. Such non-response is understandable given the circumstances. ↩

-

We’re going to omit the obvious importance of the status quo variable from consideration here. Namely, the effect is so strong it will swallow just about everything else. The Pearson’s r is .85, leading one to reasonably think of the status quo variable as kind of a latent estimation of the vote intention itself. ↩

-

Perhaps (predominantly male?) workers and students got the worst the Pinochet had to offer in terms of human rights abuses, but I cannot say that with any confidence absent more research. Gender always behaves in curious ways politically. For every instance and intuition described by a Munoz (1999), there is an apparent reality in which right-wing extremist leaders like Pinochet know exactly what they’re doing and complicate such a simple story you want to tell. I’ll have to defer on saying any more about the question other than a plea to be mindful about simple-to-the-point-of-simplistic gender stories in politics. ↩

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.