How Serious Are Americans About Democracy? An Exploratory Analysis of the AmericasBarometer Data

One of my favorite disconnects in political science—as much as you can call it that—concerns political behavior research in the United States where we see two different classes of surveys. The first, those exclusive to the United States—like the American National Election Study (ANES), Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), and General Social Survey (GSS)—ask quite granular questions about politics in the United States that are of great interest to American political behavior researchers and political commentators. They will help us understand what Americans think about things like the Trans-Pacific Partnership or gay marriage (as opposed to homosexuality, in general). I’ve used these surveys to dig at some of the more particular things Americans think about gun control, racism, abortion, and protectionism.

The second class of surveys—like AmericasBarometer or World Values Survey (WVS)—will ask effectively the same questions in the United States as it would ask in a country like Pakistan or Venezuela. This is understandable from the perspective of these researchers; the U.S. is home to arguably the most accessible public opinion data sources in the world and the marginal cost of adding a thousand or two observations in the U.S. to compare American responses to Pakistani or Venezuelan responses is quite small. However, these questions are more general, concerning bigger issues of democracy, prosperity, and security. When we use these data sources, we’re almost not interested in what the Americans are saying. The bigger concern would be developing countries where democracy is less stable and prosperity and security are not givens.

The problem with this myopia is that Americans are saying things in these surveys that we’re ignoring or treating uncritically. They’re communicating statements about American democracy that are not as optimistic or rosy as we want to think they are. My analysis, consistent with some of my hunches on what I call America’s “strong leader” problem in the WVS data, suggests attitudes about American democracy that are close to the “instrumental-intrinsic” arguments we were having about African democracy 15 years ago. Americans—partisans, in particular—may be valuing democracy and democratic norms the extent to which elections produce outcomes that partisans like. They may not be serious about democracy for democracy’s sake.

An Exploratory Analysis of Four Waves of AmericasBarometer Data

I chose the AmericasBarometer data, part of the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), to explore how partisanship conditions attitudes about democracy in the United States. Data are available in 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014, though surveys are not coherent from one wave to the next. Questions may assume a different form from one wave to the next, like the political interest variable that goes from a three-part ordinal measure to a more familiar four-part ordinal measure after the 2008 wave. Additionally, some interesting questions LAPOP would ask in the United States about populism start to disappear after the 2008 wave. Consider what follows tentative and illustrative as a result since we’ll mostly be speaking to how Republicans viewed American democracy with Obama as president. I would expand on these descriptive analyses to an inferential analysis if I knew a publication would follow. This is a bit outside my wheelhouse after all.

Co-Partisan Control of the White House Coincides with Satisfaction with Democracy (Among Republicans)

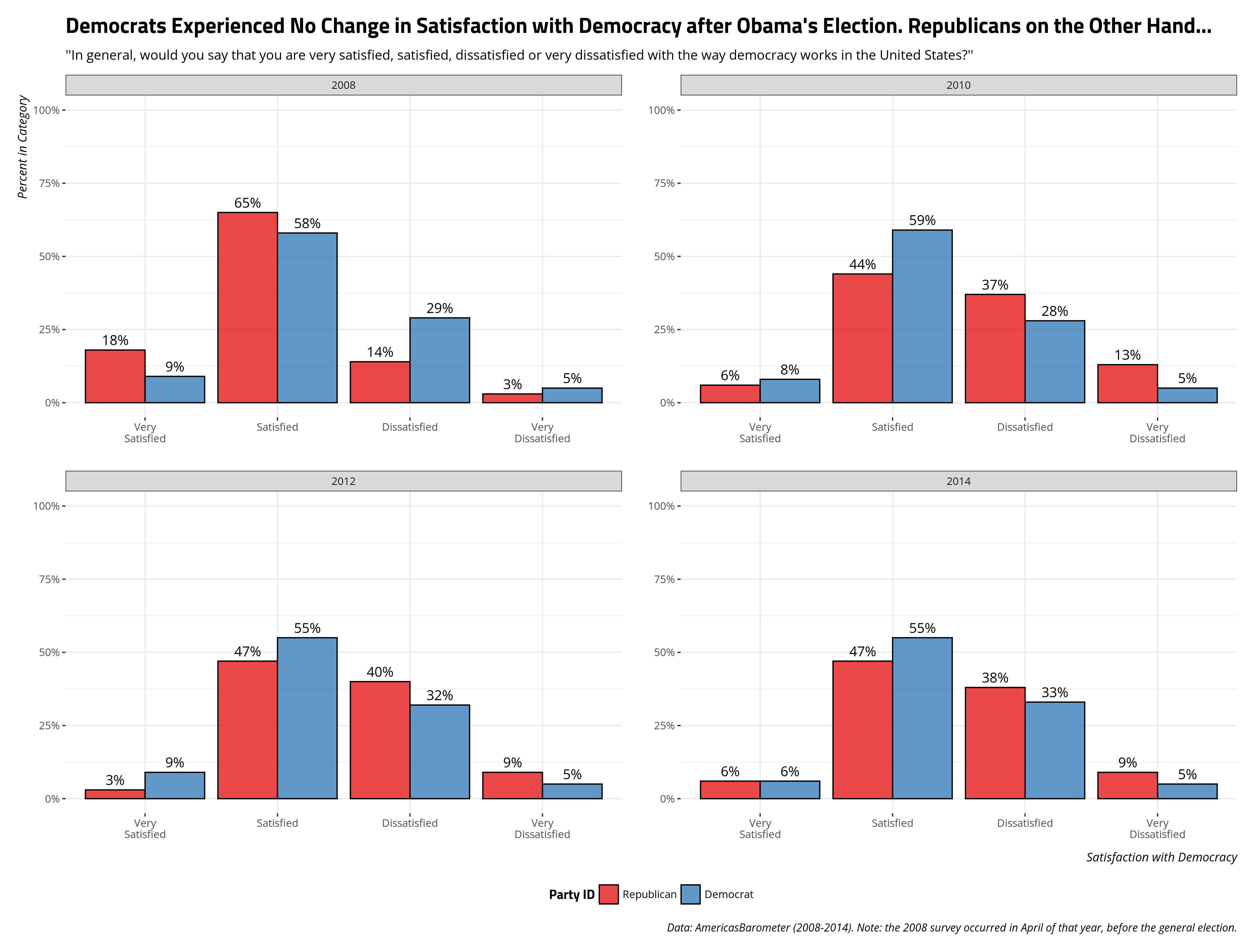

We’ll start with one of the items that does appear in all four AmericasBarometer waves under consideration here: satisfaction with the way democracy works in the United States. This question, which prompts the respondent to state their level of satisfaction with democracy on a four-part scale from “very satisfied” to “very dissatisfied”, is ubiquitous in all cross-national survey research on democracy, making it a good place to start. The figure, reproduced below, makes evident a partisan shift in democratic satisfaction after Obama’s election in 2008. Interestingly, we see this shift among Republicans and not Democrats.

The Democrats experienced no change in their level of satisfaction with democracy after Obama’s general election win gave Democrats united government. They also experienced no real shift after the Republicans took control of the House of Representatives. Republicans, on the other hand, experienced a discernible drop in their level of democratic satisfaction after Democrats took control of the White House. The percentage of cases among Republicans in the “very satisfied” group dropped from 18% to 6% in 2010. The “satisfied” group dropped from 65% to 44%. Those overall “satisfied” dropped from 83% to 50%. Democratic satisfaction after an honest election gave Democrats united government dropped to a 50/50 proposition among Republicans that did not materially improve after the Republicans retook the House.

This says more about Republicans than Democrats, per se, at the moment. Republicans conditioned their satisfaction with the way democracy works contingent on what party controlled the White House. We lack data for 2016 on this question in this survey and I’ve no doubt the results of the 2018 survey will show Democrats conditioning their level of satisfaction with democracy, in part, on what party controls the White House.

Republicans Started to Think the U.S. Was Less Democratic After Obama

We could reassure ourselves with a statement of, “well, of course partisans are dissatisfied with the way democracy works when their guy no longer sits in the White House because partisanship is a hell of a drug.” I think this is naïve and, worse yet, whitewashes a troubling statement that partisans (here: Republicans during the Obama Administration) were communicating about what they think of American democracy when it produces outcomes they do not like. If we accept the tall tales of democracy that we like to tell ourselves as the longest-running continuous democracy in the world, these patterns we observe among partisans simply proxy presidential approval. If we jettison that naïve reassurance, we see partisans might be conditioning their support for democracy based on partisan representation in government, particularly in the White House.

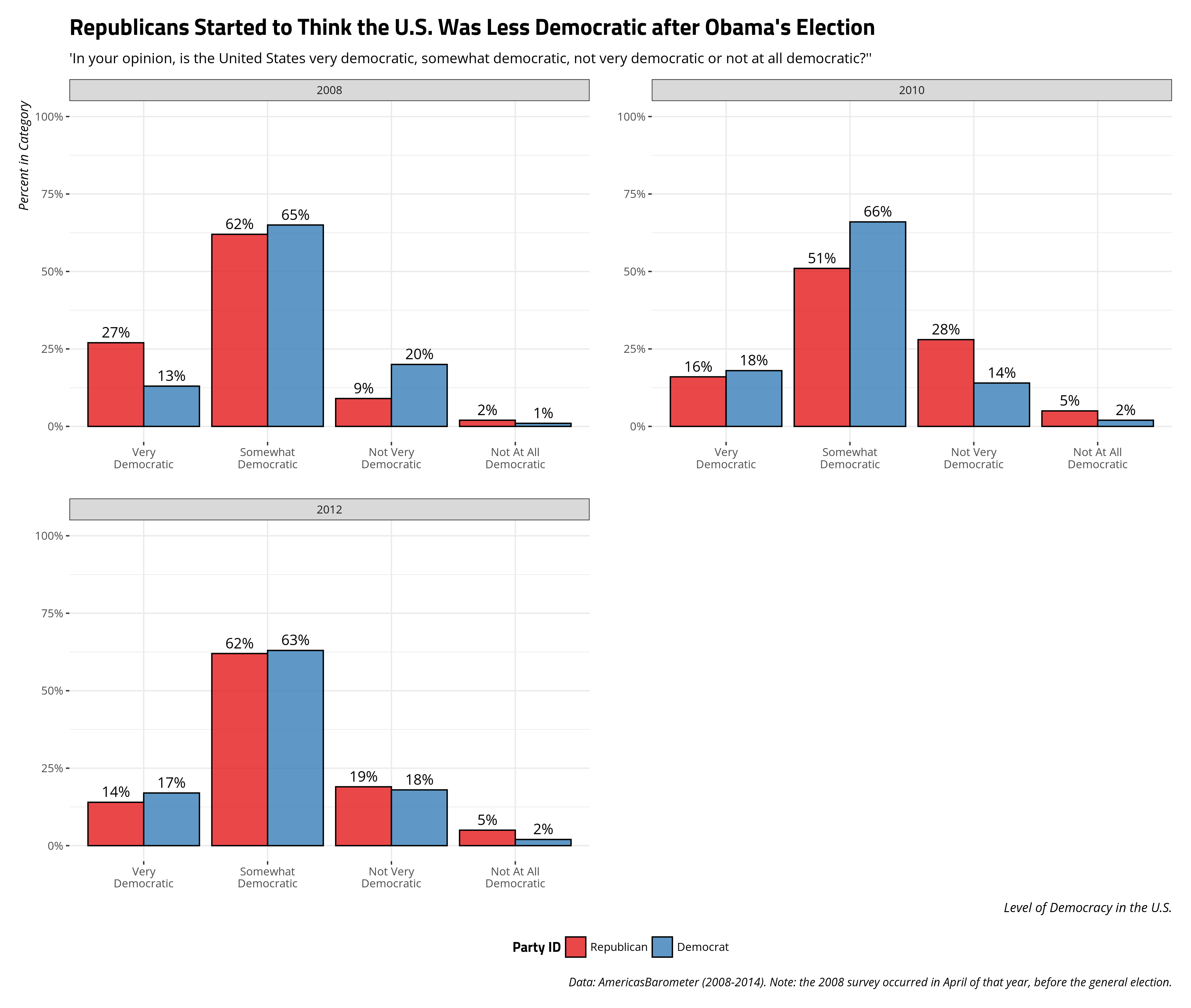

There are more patterns consistent with the latter statement than the former. AmericasBarometer asked its respondents in the 2008, 2010, and 2012 waves to state how democratic they think the United States is, in general. It regrettably dropped this question for the 2014 wave but the hope is it returns in future waves. Here, we see effectively the same pattern. Republicans are more dissatisfied with how democracy works in the U.S. after the Democrats took control of the White House and they are also more inclined to think the U.S. is less democratic after elections produce outcomes they do not like, even if this trend “corrected” a little in the 2012 wave.

We observe no such change among Democrats in these three waves. Obama’s presence in the White House and the ephemeral control of the executive and legislative branches by Democrats did not make Democrats think the U.S. was more democratic in these three waves. We should note that Democrat movement on this item, should it (hopefully) appear again in AmericasBarometer wave, would no doubt resemble what we saw of the Republican respondents in 2010.

Democrats, Like Republicans, Were More Open to Limiting the Voice and Vote of Political Opposition when Their Party Controlled the White House

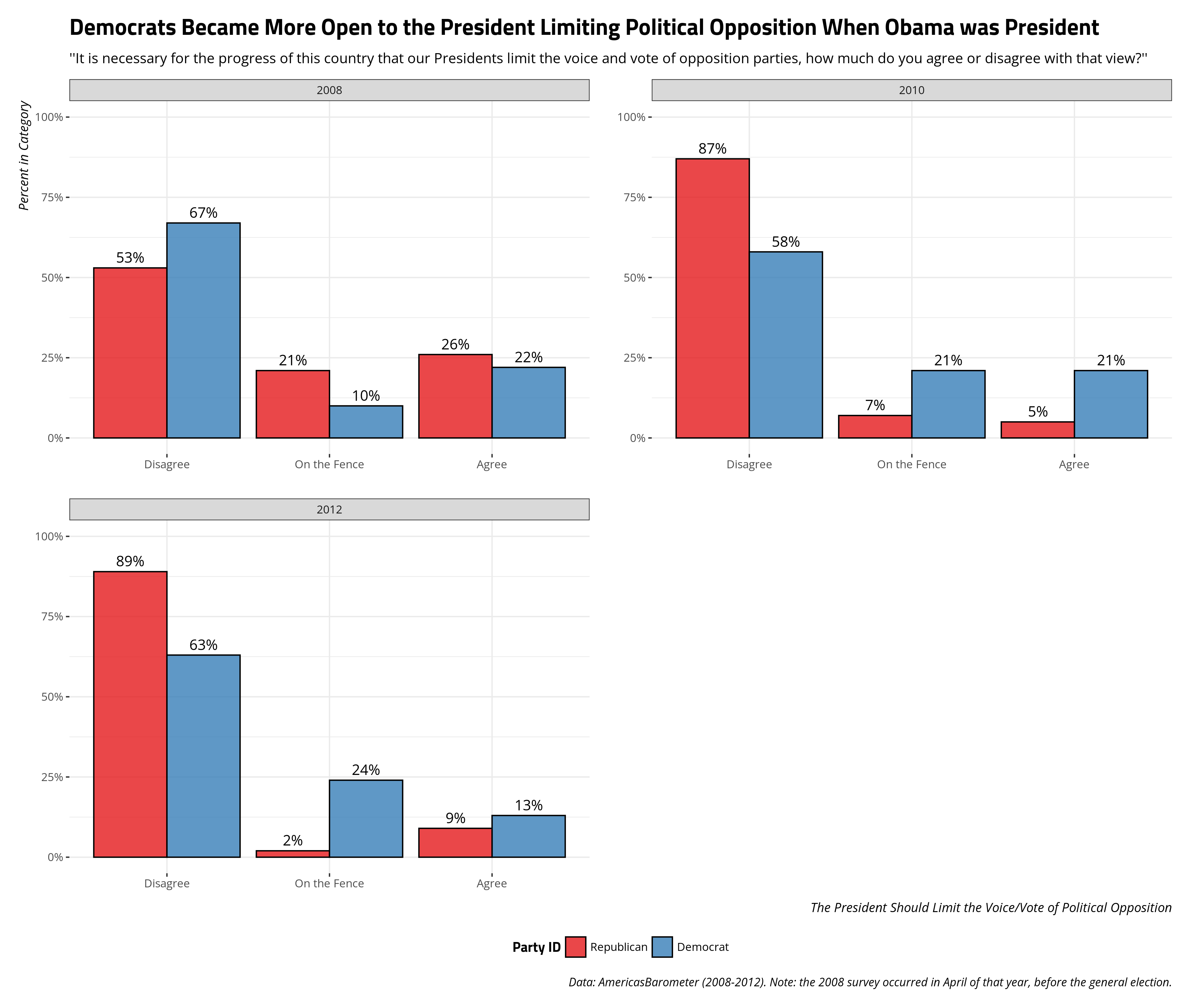

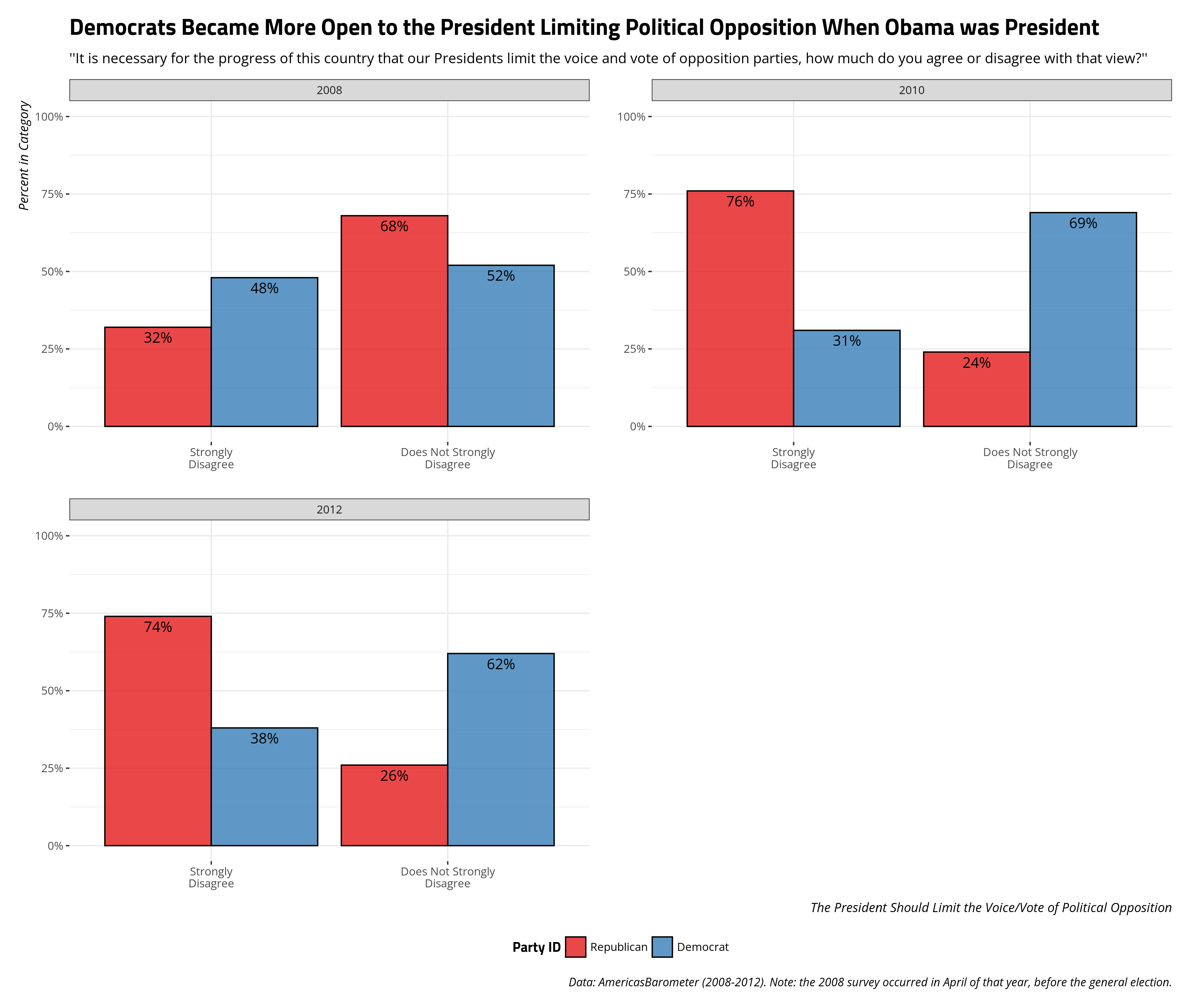

Democrats are not blameless in the AmericasBarometer data. The AmericasBarometer data are unique for asking a battery of populist questions that, regrettably, start to disappear from the questionnaire in more recent waves. The most commonly asked of these “populist” items is the following prompt: “It is necessary for the progress of this country that our Presidents limit the voice and vote of opposition parties, how much do you agree or disagree with that view?” The respondent expresses their level of agreement on a seven-item scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” For clarity and ease of interpretation (i.e. the data understandably have a discernible right skew), I condense this ordinal measure into a three-item measure that condenses values of 1-3 to “Disagree”, a value of 4 (in the middle of the possible responses) to “On the Fence” and the values of 5-7 to “Agree.”

Here, you see an important partisan sort of responses after Obama’s election. 53% of Republicans at least somewhat disagreed (per my inference) with the President silencing political opposition when George W. Bush was in office. The remainder were either on the fence (21%) or at least somewhat agreed that Bush should silence political opposition (26%). These responses, understandably, changed considerably among Republicans when Obama became president. They also changed among Democrats, who became more open to the President silencing political opposition when Obama had the position.

You could alternatively condense this to a dichotomous measure of “Strongly Disagree” vs. “Does Not Strongly Disagree” and you’ll get the same basic story. It might arguably be even “starker” because the “mostly disagree” responses would be in the same category as the “strongly agree” responses.

AmericasBarometer stopped asking this question in the United States after the 2012 wave. I wish it would return.

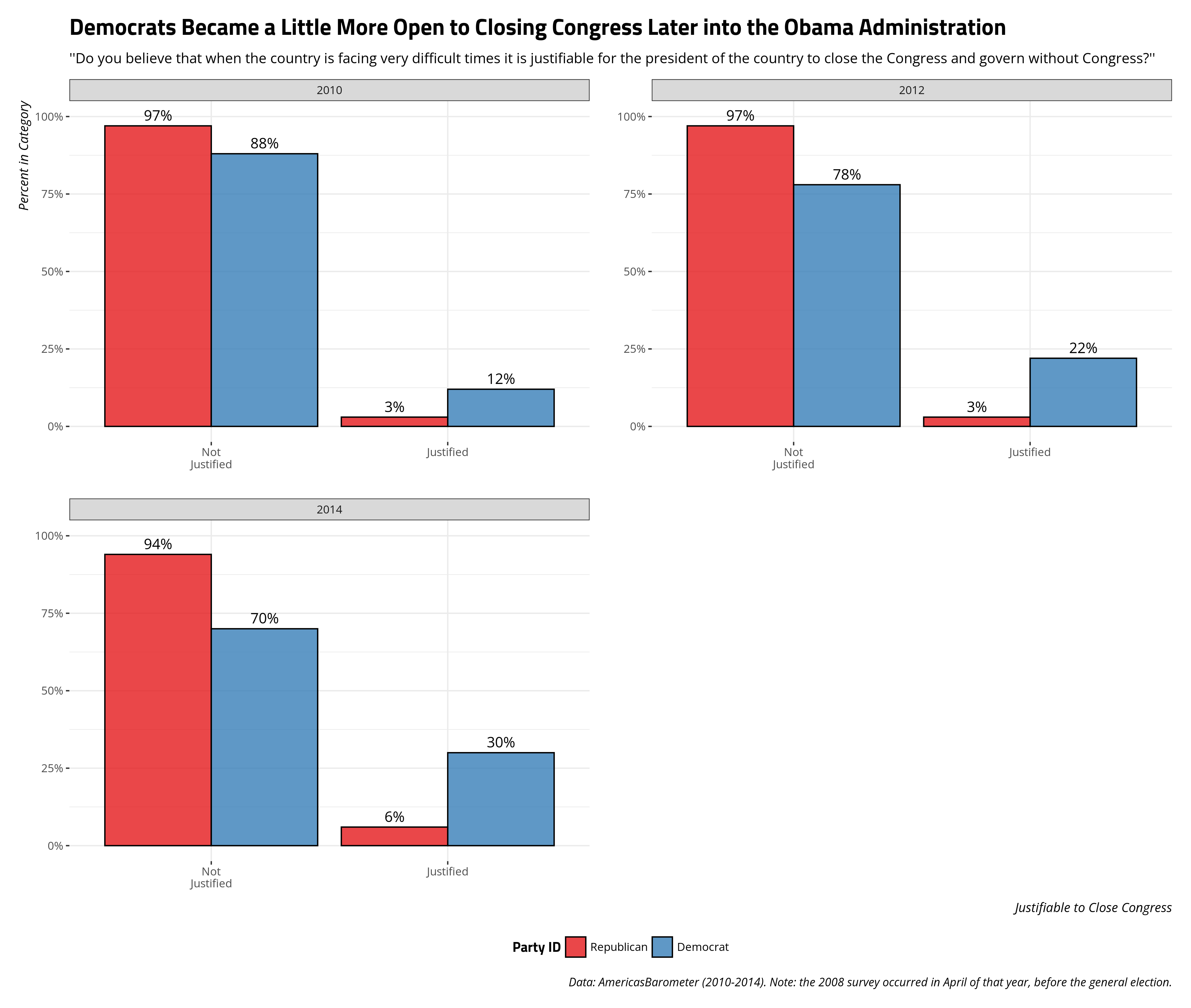

Democrats Became a Little Bit More Open to Closing Congress Later into the Obama Administration

AmericasBarometer data are again partial, but illustrative, for the purpose of this descriptive analysis. Consider this item that AmericasBarometer started asking in 2010 that dovetails nicely with some of my research. The prompt resembles familiar items from Latinobarómetro and WVS with, “Do you believe that when the country is facing very difficult times it is justifiable for the president of the country to close the Congress and govern without Congress?” The respondent can answer with “yes, it is justified” or “no, it is not justified.” Note that the question has more tooth than a similar “populist” item that talks about the President acting “without Congress.” Here, the survey item explicitly prompts the respondent to think of a situational justification for “closing” Congress and governing without the legislative body that occupied most of the Founders’ efforts in crafting the U.S. Constitution.

The good news is that most partisans are against this situational suspension of Congress even as Congress has lower approval ratings than lice and Nickelback. The bad news is there’s a clear, if small, movement among Democrats later into the Obama administration when Democrats 1) lost the House and 2) looked like they were going to lose the Senate.

We should note with morbid interest what this resembled among Democrats in 2016, or would look like among Republicans if the 2018 midterm elections result in the worst-case scenario for the GOP.

Conclusion

I worry the politics we see in the United States right now at the mass-level suggests that American partisans might not be serious about democracy. You saw it in the “Tea Party” reaction to Obama’s White House win. You’re going to see it soon among Democrats and those further to the political left with Trump in the White House, even as concerns about Trump are far more legitimate than the concerns about Obama’s united government in January 2009. Those who value democracy for democracy’s sake should not be conditioning their attitudes toward American democracy and democratic norms based on whether their co-partisans control government. Increasingly, we see this is the case. We definitely see it among Republicans. We even see it a little among Democrats in the available data, for which more recent waves will likely continue this trend.

I should note that I’m an American, and a political behavior researcher. I’m not an “American political behavior” researcher. However, my analysis suggests that those two classes of surveys in the U.S. I mentioned in the preamble—those exclusive to the U.S. and those that include the U.S. with observations from other countries—should better speak to each other. Clearly those that include the U.S. among cases like Pakistan or Venezuela could benefit from more granular and focused questions about American politics. Those exclusive to the U.S., however, may have to start questioning how committed Americans are to democracy if their responses to these general questions about democratic commitment are conditioned by co-partisan control of government. We need to start asking Americans the same questions about democracy we would ask Pakistanis and Venezuelans.

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.