'Absolute Gains or Relative Gains' Kind of Misses the Point

Last updated: 26 January 2025.

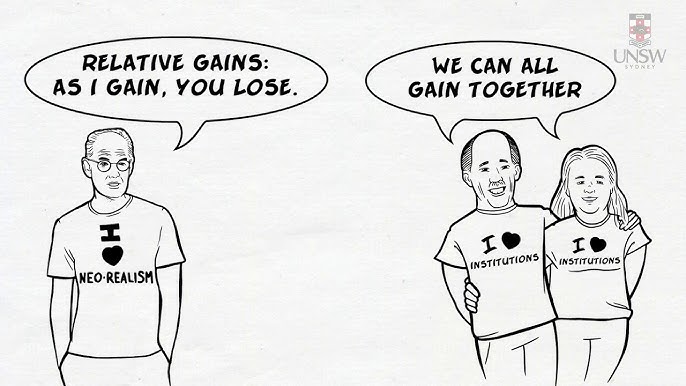

Students in my department spend a lot of time comparing/contrasting the two biggest “-isms” (so-called realism and liberalism) and the debate about whether states pursue “absolute gains” or “relative gains”. The “liberal” camp argues that states pursue “absolute gains” that benefit them overall, or words to that effect. The “realist” camp counter-argues that states do and should pursue only “relative gains” that privilege them more so than other potential rivals. There is often a discussion here about a prisoner’s dilemma, or a repeated prisoner’s dilemma that comes in tow. No matter, I remember this debate from when I was an undergraduate. I was reading the same stuff they are, and that was over 20 years ago.

I was too naive to notice this when I was an undergraduate, but I noticed it in graduate school that this debate misses the point entirely. While it looks like a “debate” that was apparently important enough to fell a lot of trees for paper to print the terms of it, this debate is rather silly and out of focus. My inspirations for this scorcher of a 🔥 #take come from R. Harrison Wagner and Robert Powell’s different approaches to this stuff. I’ll (try to) elaborate.

For one, Wagner (2007, p. 41-2) will repeat some of the points made by Powell (to follow), though fn. 60 emphasizes one major reason why I think this debate misses the point. If you come from a bargaining perspective, all gains are relative because all goods are divisible. No good that is important enough to potentially be militarized could be anything but divisible, and the division of it produces gains that can only be relative. That is: goods are zero-sum. In the classic case that I like to teach, two states are trying to proverbially divide a dollar and maximize their individual payouts in the process. The proverbial dollar could be the openness of State B to State A’s goods. It could be the division of territory. No matter what, there is no division possible of the good in question in which both sides are better off. One side getting a better deal means another side is getting a worse deal. Zero-sum goods can only produce “relative gains” in that way.

Thus, I think so-called liberal argumentation in the abstract about the downstream benefits of cooperation misses an important point, or at least loses sight of it in the confines of the debate they elect to have. A payout downstream from an agreement is a dividend, not an absolute gain in the terms in which it’s often discussed. Consider the 1993 agreement between China and India regarding their contentious border. The agreement reaffirmed the status quo, one largely imposed on India by China following the failed “push” in 1962. However, the confirmation of the status quo comes in relation to all of what India covets. Accepting the status quo in terms of what was conceivably on the table is a relative loss for India. China got more (i.e. it retains what it has). India got less than it wants (which is a loss). Just because there’s been some kind of goodwill that’s followed from that doesn’t change the fact the division of a good is ultimately relative. “Absolute gains or relative gains” obscures more than it reveals.

Powell’s 1991 article and 1994 article are must-reads on this topic as I think he does a great job making clear how much is unclear or poorly stated in what’s superficially a really obvious debate. The 1991 article offers a simple framework for thinking about the problem while noting the terms of the debate are wholly divorced from the methods being used. The debate occurs using similar methods as economists might use studying the behavior of firms under conditions of perfect competition or monopoly. However, neither strategic context changes the incentive that economists impute for a firm. It’s always about maximizing profit. Thus, a debate about apparent behavior that is observed is not an empirical debate about what states “do”. It’s actually a debate about what assumptions we elect to make about what they do. We’re altering their preferences and not their behavior, per se, and debating the relative merits of these competing assumptions. If this is what we elect to do, it’s important to say outright we’re always going to talk past one another. Why are we having this debate, then? It’s no longer a debate about empirics, which can be resolved (in principle, contingent on other assumptions). It’s a debate about what we assume states do, and we’re not going to resolve that anymore than we’d resolve a debate about the perspectives we have toward the world.1

Powell (1991) may not be drinking the same amount of vinegar that Wagner (2007) or myself would binge on this next point, but he also addresses the fact that both these competing arguments aren’t thinking through their mechanisms in important detail.2 So-called realists and liberals are imputing different assumptions about preferences but using the same basic model in its most rudimentary form to emphasize their claims. Yes, this is the “prisoner’s dilemma”.3

You can search for an illustrative story to tell around this normal form game and payoff matrix, but here’s what they would typically look like for Player 1 (row player, first payout in a given cell) and Player 2 (column player, second payout in a given cell).

\[\begin{array}{c c} & \begin{array}{c c} C & D \end{array} \\ \begin{array}{c c} C \\ D \end{array} & \left[ \begin{array}{c c } -1, -1 & -10, 0\\ 0, -10 & -5, -5 \end{array} \right] \end{array}\]If you do the rote thing we teach students re: game theory, the Nash equilibrium emerges in the bottom right. Both players chose “D”. “D”, as a stand-in for “defect”, is incidentally the dominant strategy. It’s the best response for each player no matter what the other does. Player 1 can choose “C” (a stand-in for “cooperate”), and “D” still results in a better payout for Player 2. Preferences here are symmetric, so the same holds for Player 2 vis-a-vis Player 1. If we arrive in that bottom right cell where both players choose “D”, there is no unilateral incentive to change behavior for any player. Mutual defection is the only equilibrium outcome of this simple game even if mutual cooperation is the Pareto optimal outcome.

But what if we “repeat” this game three times? If so, the payout for this equilibrium outcome is -15 for both. If both players had avoided temptation and chosen “C”, even if “D” is the dominant strategy, the payout across three iterations is -3. As an illustration of so-called “liberal” claims in the most basic form, mutual cooperation carries costs but is long-run beneficial.

This sounds great until you realize there are a few limitations with this exercise and what it can ultimately tell us for either side of the debate. One point about the overall systemic consistency in which we are playing this game is a point that Powell elaborates in his 1994 article, and I’ll save that for the next paragraph. Another is that we have no vehicle within a simple setup like this for liberals to dismiss away realist claims about concerns for relative gains. A minimal setup like this focuses on a simplistic assessment about the long-run utility of cooperation over conflict but doesn’t dismiss realist critiques converting “absolute gains” into “relative gains”, whatever that might look like at a later time. Realists themselves are unclear why this must always be the case in the confines of this debate, or even what this might look like more concretely. A bargaining perspective might highlight that both sides are undertheorizing what exactly commitment problems look like in international politics. Realists seem to attribute this to the absence of a hegemon, which would invoke a constant to explain something that varies. Some days, it’s hard to look at Keohane and Martin (1995) and not wonder if they’re begging the question in the same manner.

“Institutions matter”, but the argument often reduces to some kind of ex machina device the authors invoke like realists would use with anarchy. Consider this passage from Keohane and Martin (1995, 42):

Institutions can provide information, reduce transaction costs, make commitments more credible, establish focal points for coordination, and in general facilitate the operation of reciprocity. By seeking to specify the conditions under which institutions can have an impact and cooperation can occur, institutionalist theory shows under what conditions realist propositions are valid. It is in this sense that institutionalism claims to subsume realism.

I’m sorry, but what even is this? I think it’s important to note the first sentence is 100% correct, certainly for how economists would think about the important costs that go into making any transaction. However, how is this any different from something a realist would say (and also not explain well)? It doesn’t help the reader that this article is as equally deferential to realism’s place in the academy as it tries to distinguish itself from it. The reader may just be looking at two Spidermans pointing at each other with the same level of information as you’d get from a PNG copy of that meme.

The last point here is more meta. The options are always the same in this simple game. Rather than play it once, we’ve played it three times and always with the same choices. But that isn’t international politics, no? Any “prisoner’s dilemma” in which one side can eliminate the other is no longer a prisoner’s dilemma. It’s something else entirely. The insight we hope to draw from this simple game is simple to the point of simplistic. Simple is good; simplistic is bad It’s fitting that we teach prisoner’s dilemmas in the context of criminal situations, because mafias have done well to figure this problem out. There isn’t a second time; there are just dead bodies.

Powell (1994) expands on this in reviewing another salvo in this debate. The article itself is multiple and touches on several issues dividing so-called realists and liberals, but he also emphasizes that we’ve been mistaking effects for causes. Seeking absolute gains or relative gains, however defined, is a function of the security environment and concerns states may have about things like the security dilemma or the offense-defense balance. Thus, we can assume that states are concerned with relative gains, but then the degree to which it’s concerned with relative gains becomes an outcome to be explained. When cause and effect are conflated, the question we’re begging is poorly understood.

I might expand on this more. There’s a lot more than can be said about the difference between what states “do” and what they “should do”. No matter, I at least want this here for now for when it comes up in class. “Absolute gains or relative gains” is a debate that misses the point entirely. I don’t think what we elect to discuss in the confines of this apparent debate is a productive use of energy at all.

-

I have a previous blog post that talks to students about perspectives as a kind of proto-theory. The language would dove-tail with Wagner’s (2007, 42) dismissal of this debate that an empirical test of an “approach” is not possible. ↩

-

Anarchy is also a constant and is not now, nor has it ever been, a necessary condition for war. Related: states, as institutions, might be born from war but are not necessary conditions for war either. Wagner (2007, chp. 1) is useful as a broad historical outline of the realist fixation with anarchy by way of 1) the emerging discipline’s need to distinguish itself from the “hierarchy” of national politics and 2) Waltz’s inspiration in Rousseau, not in Hobbes. Seriously! Waltz (1959, 232) begs the question by assuming anarchy leads to war because anarchy means nothing prevents war from happening. On this basic point about cooperation under anarchy, Keohane and company (c.f. Keohane, 1984; Axelrod and Keohane, 1986) are importantly, if minimally, correct about the realist inability to think beyond a basic conjecture that anarchy means the absence of cooperation. I’ll credit Glaser (1996) for at least trying to salvage a so-called realist path toward cooperation, but his effort is awkward for a few reasons. What he offers is somewhere between an attempt to perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on a baby that’s drowned in the bathwater for 30 minutes, or Jimmy Valmer’s effort to reconcile rival gang warfare with a rec center lock-in. It’s not lost on me that Glaser wrings hands about what this would look like in the most abstract terms, but is avoiding to his level-best any effort to say what this looks like as an institutional manifestation. “Self-help could lead to cooperation”. Okay, but how? ↩

-

This too has an interesting origin story in international relations. Realists love this particular model to illustrate its core claims about cooperation since non-cooperation is a dominant strategy in these games. However, we don’t have Waltz or any so-called realist to thank for this insight, but we do have them to blame for taking this model and running with it as a basic confirmation of their thesis (Wagner 2007, 41). Instead, we have the international political economy folks like Kindleberger (1973) and Gilpin (1975) to thank for formalizing realist arguments on the behalf of realists. Gatekeeper effects are well-known to those of us in the academy, but the extent of them are underappreciated. ↩

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.