An R Markdown Template for Academic Manuscripts

An Updated Version of This Template is in {stevetemplates} ⤵️

This template is available in {stevetemplates}, an R package that includes all my R Markdown templates. The version of the template available in the package is slightly modified/improved from what I present here. I also want to note that I do not intend to offer too much support for this template, in light of my newer article template that is also available in {stevetemplates}. Issues with this template can be best addressed on the project's Github.

You should consider no longer using LaTeX as a front-end for your manuscripts. Use a wrapper for LaTeX instead, like R Markdown.

I’ve discussed a previous move from LaTeX’ Beamer package to R Markdown, but was otherwise deferential to standard LaTeX for documents. However, LaTeX is ugly code. My manuscripts were also succumbing to “preamble creep”. My preambles kept getting bigger and messier with each successive manuscript. Standard LaTeX also can’t speak to R. A manuscript may require a careful and manual rewrite of the manuscript to better conform to the changes in the analysis.

I’ve started writing all my manuscripts now in R Markdown, which eliminates both markup (hence: “Markdown”) and allows me to better work with collaborators. In what follows, I discuss the properties of a template I wrote to render my PDFs and how LaTeX users could incorporate it into their own research workflow. I start with the YAML properties of my template and then discuss some basic Markdown syntax. I show what my Markdown academic manuscript template resembles in a full PDF thereafter. This PDF mirrors the post here but contains an extended discussion at the beginning of what R Markdown can do for issues of workflow. The PDF also contains examples how to execute R within the Markdown document. This type of “dynamic document” allows for the author to write the manuscript and reproduce the analysis in one fell swoop.

You can find the example .Rmd file, the example PDF, and my academic manuscript template on my Github at this repository.

Getting Started with YAML

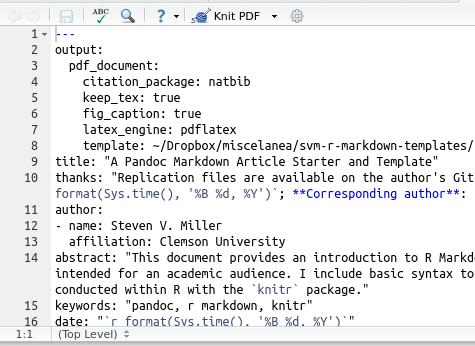

The lion’s share of a R Markdown document will be raw text, though the front matter may be the most important part of the document. R Markdown uses YAML for its metadata and the fields differ from what an author would use for a Beamer presentation. I provide a sample YAML metadata largely taken from this exact document and explain it below.

---

output:

pdf_document:

citation_package: natbib

keep_tex: true

fig_caption: true

latex_engine: pdflatex

template: ~/Dropbox/miscelanea/svm-r-markdown-templates/svm-latex-ms.tex

title: "A Pandoc Markdown Article Starter and Template"

thanks: "Replication files are available on the author's Github account..."

author:

- name: Steven V. Miller

affiliation: Clemson University

- name: Mary Margaret Albright

affiliation: Pendelton State University

- name: Rembrandt Q. Einstein

affiliation: Springfield University

abstract: "This document provides an introduction to R Markdown, argues for its..."

keywords: "pandoc, r markdown, knitr"

date: "`r format(Sys.time(), '%B %d, %Y')`"

geometry: margin=1in

fontfamily: mathpazo

fontsize: 11pt

# spacing: double

bibliography: ~/Dropbox/master.bib

biblio-style: apsr

---output: will tell R Markdown we want a PDF document rendered with LaTeX. Since we are adding a fair bit of custom options to this call, we specify pdf_document: on the next line (with, importantly, a two-space indent). We specify additional output-level options underneath it, each are indented with four spaces. citation_package: natbib tells R Markdown to use natbib to handle bibliographic citations.1 Thereafter, the next line (keep_tex: true) tells R Markdown to render a raw .tex file along with the PDF document. This is useful for both debugging and the publication stage, when the editorial team will ask for the raw .tex so that they could render it and later provide page proofs. The next line fig_caption: true tells R Markdown to make sure that whatever images are included in the document are treated as figures in which our caption in brackets in a Markdown call is treated as the caption in the figure. The next line (latex_engine: pdflatex) tells R Markdown to use pdflatex and not some other option like lualatex. For my template, I’m pretty sure this is mandatory.2

The next line (template: ...) tells R Markdown to use my custom LaTeX template.3 While I will own any errors in the code, I confess to “Frankensteining” this template from the default LaTeX template from Pandoc, Kieran Healy’s LaTeX template, and liberally using raw TeX from the Association for Computing Machinery’s (ACM) LaTeX template. I rather like that template since it resembles standard manuscripts when they are published in some of our more prominent journals. I will continue with a description of the YAML metadata in the next paragraph, though invite the curious reader to scroll to the end of the accompanying post to see the PDF this template produces.

The next fields get to the heart of the document itself. title: is, intuitively, the title of the manuscript. Do note that fields like title: do not have to be in quotation marks, but must be in quotation marks if the title of the document includes a colon. That said, the only reason to use a colon in an article title is if it is followed by a subtitle, hence the optional field (subtitle:). Notice I “comment out” the subtitle in the above example with a pound sign since this particular document does not have a subtitle. If thanks: is included and has an accompanying entry, the ensuing title of the document gets an asterisk and a footnote. This field is typically used to advise readers that the document is a working paper or is forthcoming in a journal.

The next field (author:) is a divergence from standard YAML, but I think it is useful. I will also confess to pilfering this idea from Kieran Healy’s template. Typically, multiple authors for a given document are separated by an \and in this field. However, standard LaTeX then creates a tabular field separating multiple authors that is somewhat restrictive and not easy to override. As a result, I use this setup (again, taken from Kieran Healy) to sidestep the restrictive rendering of authors in the standard \maketitle tag. After author:, enter - name: (no space before the dash) and fill in the field with the first author. On the next line, enter two spaces, followed by affiliation: and the institute or university affiliation of the first author.

Do notice this can be repeated for however many co-authors there are to a manuscript. The rendered PDF will enter each co-author in a new line in a manner similar to journals like American Journal of Political Science, American Political Science Review, or Journal of Politics.

The next two fields pertain to the frontmatter of a manuscript. They should also be intuitive for the reader. abstract should contain the abstract and keywords should contain some keywords that describe the research project. Both fields are optional, though are practically mandatory. Every manuscript requires an abstract and some journals—especially those published by Sage—request them with submitted manuscripts. My template also includes these keywords in the PDF’s metadata.

date comes standard with R Markdown and you can use it to enter the date of the most recent compile. I typically include the date of the last compile for a working paper in the thanks: field, so this field currently does not do anything in my Markdown-LaTeX manuscript template. I include it in my YAML as a legacy, basically.

The next items are optional and cosmetic. geometry: is a standard option in LaTeX. I set the margins at one inch, and you probably should too. fontfamily: is optional, but I use it to specify the Palatino font. The default option is Computer Modern Roman. fontsize: sets, intuitively, the font size. The default is 10-point, but I prefer 11-point. spacing: is an optional field. If it is set as “double”, the ensuing document is double-spaced. “single” is the only other valid entry for this field, though not including the entry in the YAML metadata amounts to singlespacing the document by default. Notice I have this “commented out” in the example code.

The final two options pertain to the bibliography. bibliography: specifies the location of the .bib file, so the author could make citations in the manuscript. biblio-style specifies the type of bibliography to use. You’ll typically set this as APSR. You could also specify the relative path of my Journal of Peace Research .bst file if you are submitting to that journal.

Getting Started with Markdown Syntax

There are a lot of cheatsheets and reference guides for Markdown (e.g. Adam Prichard, Assemble, Rstudio, Rstudio again, Scott Boms, Daring Fireball, among, I’m sure, several others). I encourage the reader to look at those, though I will retread these references here with a minimal working example below.

# Introduction

**Lorem ipsum** dolor *sit amet*.

- Single asterisks italicize text *like this*.

- Double asterisks embolden text **like this**.

Start a new paragraph with a blank line separating paragraphs.

- This will start an unordered list environment, and this will be the first item.

- This will be a second item.

- A third item.

- Four spaces and a dash create a sublist and this item in it.

- The fourth item.

1. This starts a numerical list.

2. This is no. 2 in the numerical list.

# This Starts A New Section

## This is a Subsection

### This is a Subsubsection

#### This starts a Paragraph Block.

> This will create a block quote, if you want one.

Want a table? This will create one.

Table Header | Second Header

------------- | -------------

Table Cell | Cell 2

Cell 3 | Cell 4

Note that the separators *do not* have to be aligned.

Want an image? This will do it.

`fig_caption: yes` will provide a caption. Put that in the YAML metadata.

Almost forgot about creating a footnote.[^1] This will do it again.[^2]

[^1]: The first footnote

[^2]: The second footnote

Want to cite something?

- Find your biblatexkey in your bib file.

- Put an @ before it, like @smith1984, or whatever it is.

- @smith1984 creates an in-text citation (e.g. Smith (1984) says...)

- [@smith1984] creates a parenthetical citation (Smith, 1984)

That'll also automatically create a reference list at the end of the document.

[In-text link to Google](http://google.com) as well.That’s honestly it. Markdown takes the chore of markup from your manuscript (hence: “Markdown”).

On that note, you could easily pass most LaTeX code through Markdown if you’re writing a LaTeX document. However, you don’t need to do this (unless you’re using the math environment) and probably shouldn’t anyway if you intend to share your document in HTML as well.

The Template in Action

This is what the template looks like in action. You can also find how to use R Markdown and knitr to run R code within your R Markdown document, allowing for dynamic report generation.

Refer to my Github and my template repository for future updates.

-

R Markdown can use Pandoc’s native bibliography management system or even

biblatex, but I’ve found that it chokes with some of the more advanced stuff I’ve done with my .bib file over the years. For example, I’ve been diligent about special characters (e.g. umlauts and acute accents) in author names in my .bib file, but Pandoc’s native citation system will choke on these characters in a .bib file. I effectively neednatbibfor my own projects. ↩ -

The main reason I still use

pdflatex(and most readers probably do as well) is because of LaTeX fonts. Unlike others, I find standard LaTeX fonts to be appealing. ↩ -

Notice that the path is relative. The user can, if she wishes, install this in the default Pandoc directory. I don’t think this is necessary. Just be mindful of wherever the template is placed. Importantly,

~is used in R to find the home directory (not necessarily the working directory). It is equivalent to saying/home/stevein Linux, or/Users/steveon a Mac, in my case. ↩

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.