Global Governance and the International Politics of Standard Reference Temperature

- Think the meter is kind of boring? It was the subject of an interesting political fight in the early 1900s about *when* something is a meter.

I’m writing this because I have to get ready for the semester coming up. My department’s second sequence in its first-semester track is a discussion of global governance. This is kind of a challenge for this particular international relations scholar, who is more interested in talking about international conflict. It’s also very much rooted in the -isms. Neither of those are my cup of tea.

I found a way to make this somewhat interesting to me. Clearly, questions of human rights and the environment are more important in the study of international cooperation. However, “global governance” people caution that the governance of the world is more than just the really big stuff that appears before the United Nations. Indeed, global governance pervades our lives in some mundane ways we take for granted, like the standardization of basketball, signals of creditworthiness, and even our domain names. If you know where to look, you’ll find global governance stories everywhere in ways that can be quite interesting. Even in the meter.

Yes, the meter and, to be more specific, when something is a meter long. Defining the meter was subject to an interesting political fight at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. There are important technical and scientific questions here, but there’s also a political story you could shoehorn into an international relations lecture as I do. What follows is a fleshed out version of the bit in lecture I give to students. I’m writing it here so I can point students here after lecture.

There will be some R code here, using these packages.

library(tidyverse) # for most things

library(peacesciencer) # for using CoW's NMC data

library(stevethemes) # for my custom themes

library(kableExtra) # for a table

theme_set(theme_steve())

Importantly, I want to draw attention to this article by Ted Doiron (2007) in the Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standard and Technology. I’ll make ample reference to this article for details and specifics. Doiron is providing the important historical and technical information to support this post of mine. I’m just largely telling a political story on top of it and communicating its suitability to an international relations audience.

Here’s a table of contents.

- Some Background on Measurements, the Meter, and Standard Reference Temperature

- The Political Fight(s) over Standard Reference Temperature

- The So-Called “-isms” and the Global Governance of Standard Reference Temperature

- Conclusion

Some Background on Measurements, the Meter, and Standard Reference Temperature

The story here has to assume some background. By this point in a lecture, I will have introduced students to the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM). This is one of the older inter-governmental organizations (IGOs) in the Correlates of War data. It is the seventh oldest by formation and fourth oldest among those still in existence (behind the Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine [CCNR], the International Telecommunications Union [ITU], and the Universal Postal Union [UPU]).

Here, for example, are the first ten IGOs in the CoW data.

cowIGO <- haven::read_dta("~/Koofr/data/cow/igo/3/igo_year_format_3.dta")

# ^ data current as of 2014

cowIGO %>%

mutate(lastyear = max(year), .by = ioname) %>%

arrange(year) %>%

slice(1, .by=ioname) %>%

select(ioname:year, lastyear)

| IGO (Abbr.) | IGO Name | Year Formed | Last Year (2014 = Ongoing) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCNR | Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine | 1816 | 2014 |

| SCH | Superior Council of Health | 1838 | 1914 |

| ECCD | Euro Comm for Control of Danube | 1856 | 1939 |

| ICCSLT | Intl Comm of Cape Spartel Light | 1865 | 1958 |

| ITU | Intl Telecom Union | 1865 | 2014 |

| UPU | Universal Postal Union | 1874 | 2014 |

| BIPM | International Bureau of Weights Measures | 1875 | 2014 |

| IPentC | Intl Penitentiary Comm | 1875 | 1951 |

| IUPR | Intl Union of Pruth | 1878 | 1914 |

| ICPTU | Intl Conf Promoting Tech Unification | 1882 | 1938 |

I hope it’s not lost on the reader, or my students, that there is no telling a story about the rise of intergovernmental organizations without telling a story about the consequences of war (CCNR, and see also: the European Commission for Control of the Danube [1856-1939]) or advances in technology that necessitate some kind of coordination about things that we might take for granted. Who among us sweats the details of telegraphic networks (ITU), international mail delivery (UPU), or, in this case, what exactly is a meter or gram (BIPM). However, these are important details to sweat as they emerge. In the context of meters and grams, they are critical details to sweat with the rise of global trade in the 19th century. If I’m paying to import something that has some specified length, we should all agree on what exactly the length is. That was the initial mission of BIPM, a France-hosted IGO for coordinating measurement standards of the International System of Units.

The follow-up question of “what is a meter?” has its own interesting historical trajectory by the end of the nineteenth century. In fact, the history of measurement is its own fascinating Wikipedia entry and those of us who had to read the Bible in our youth remember some oddball measurements mentioned in those texts. However, it’s the French who largely pioneered the measurements we use today. The formation of the meter is based around an aim to standardize measurements to natural phenomena. In the case of the meter, it was originally understood as one ten-millionth of the shortest distance from the North Pole to the equator for a line passing through Paris. This definition changed through time and with more precise measurements. By 1889, the benchmark for the meter became a particular bar made of platinum and iridium. Formally, the meter was the length of the bar you see to the right 1) supported by two cylinders of a diameter of at least one centimeter, 2) placed 571 millimeters apart, and 3) measured at the melting point of ice (0 °C, or 32 °F).1

It’s the third component that will likely stand out to the reader and student. Why this temperature? This has two answers. First, remember the principle of thermal expansion you learned about in school. Most things generally expand when heated and contract when cooled (water is the most obvious exception). Each element has some kind of coefficient of thermal expansion you’d have to know. Long story short: there is no knowing how long a meter is without knowing the temperature for which something is a meter long. Second, consider the time. Thermometry was somewhat unreliable at the time and only two measurements were known with some kind of precision: the boiling point of water and the melting point of ice. Of the two, the melting point was more easily reproducible because it is 3,700 times less dependent on atmospheric pressure. As a technical matter, it would be the only standard reference temperature that would make sense at this time.

The Political Fight(s) over Standard Reference Temperature

Given popular conceptions about measurement in the United States, the role of the United States as protagonist in this story about the meter and the change to 20 °C as the standard reference temperature is prima facie bizarre. No matter, that’s the role I’ll argue it served here.

The use of 0 °C as the standard reference temperature irked bureaucrats and metrologists in the United States for many reasons. The United States was a charter member of BIPM and one of the original 17 signatories to the Metre Convention. It definitely had its customary units in place come 1832, but it was aware of how conspicuous its use was relative to measurement in Europe. The Metric Act of 1866 protected the metric system especially because manufacturers in the United States were targeting export markets that would never use the U.S. customary units. Thus, the United States was never against metric measurements in this fight it had with the BIPM. Instead, it had legal and administrative requirements imposed on bureaucrats and metrologists to standardize and replicate the meter relative to its customary units.

From the American perspective, 0 °C was strange for a standard reference temperature. Nothing of interest to export-oriented manufacturers in the U.S. at the time was made in freezing conditions. Some things, like steel and brass, have very different coefficients of thermal expansion that would wreak havoc on assembly if assembly were happening at 0 °C to be used or re-assembled at some kind of room temperature. Why not use room temperature under those circumstances? American efforts to reproduce the meter at something analogous to room temperature (let’s say: 20 °C) required understanding how their reproductions squared with the real thing at 0 °C. Domestic law somewhat impelled the U.S. metrologists and bureaucrats to verify their replication for the sake of metrification.

However, approaches by metrologists and public officials from the United States to the BIPM to check their work were met with a cold shoulder. Consider this exchange from Charles-Édouard Guillaume, secretariat of the BIPM, to Samuel Wesley Stratton (pp. 2-3):

But comparisons cannot be made with International Prototype. The International Prototype Meter as well as the kilogram, and their certificates, are shut up in a depository, which is under the charge of the International Committee, and closed by three locks, one key of which is in my hands, the second is deposited in the Archives of France, and the third is in possession of the President of the Committee, Prof. Foerster at Berlin. The depository which is a deep cave under our laboratory, is inaccessible to me as well as to all the world. It cannot be opened and much more the prototype can not be taken out except by a decision of the Committee in session.

The BIPM wanted this issue to go away and pleaded practicality to advocate a philosophical position about the inherent rightness of 0 °C. Interestingly, the BIPM tried to shut up the Americans once and for all at its 29th meeting in 1913. Therein (p. 90), the BIPM insisted on the melting point of ice as the standard reference temperature for defining the meter. However, this wasn’t enforced in light of events to follow. The BIPM, which had met every two years prior to this point, would not convene again until 1920 for obvious reasons.

There were both technical and bureaucratic reasons for why the move from 0 °C to 20 °C stalled. Again, thermometry was far more uncertain at the end of the 19th century than it is now and there were only a handful of replica bars circulating around the world for Americans to benchmark their meter for their own legal requirements. Doiron’s (p. 3) treatment here suggests a schism between the practical demands of industry and metrologists in the United States to the philosophical aims of BIPM scientists on this matter. It’s the difference of “this isn’t useful” versus “this is right”. Doiron’s treatment doesn’t mention this, but there’s an air of a power play by France as well as their metrologists were adamant about 0 °C. They had the bar, and perhaps the philosophical was practical for them. They could more easily reproduce replications of the meter (their meter) at 0 °C. Metrologists and public officials in the United States had their own political pressures, and political aims. So did the French and the IGO it housed.

No matter, it seems that only France and the experts at the IGO it housed held to this position of 0 °C for standard reference temperature. Elsewhere, the Brits proposed a standard reference temperature of 62 °F· The roles have definitely reversed, but the metrologists of the United Kingdom were far more adamant about the use of Fahrenheit for standard reference temperature than American metrologists were at the time. From a correspondence from Stratton to his counterpart in the United Kingdom about the British proposal (pp. 4-5):

Referring to your letter of August 17, 1916, in regard to a suitable standardization temperature for commercial metric standards of length, I have to say that we have carefully read Mr. Sears’ memorandum, and while we agree with him that commercial standards of length, whether metric or English, should be standardized at the temperature at which they are to be used, we do not concur in his opinion that the mean workshop temperature to be se1ected should be 62 °F.

There is, at the present time, a decided tendency away from the Fahrenheit temperature scale, and we feel that the tendency should be encouraged. There is, in fact, a bill now pending in Congress by which it is hoped to abolish the Fahrenheit scale, at least from Government publications.

The temperature 20 °C is coming more and more to be accepted as the standard temperature for industrial as well as scientific operations. The sugar industry, for example, is practically on the 20 °C basis. All polariscopic tubes, flasks, etc. used in making up sugar solutions are made standard at that temperature. Very many hydrometers are standard at this temperature and the glass volumetric apparatus standardized by this bureau is on that basis and has been for the past ten years or sore. Also many of the steel tapes used in this country are standard at 20 °C.

I might add many other examples to show that 20 °C is being largely accepted as the standard temperature in scientific and technical work. Would it not, therefore, under the circumstances, be better to standardize both the English and metric commercial standards on this basis rather than that of 62 °F? 20 °C would certainly have a very great advantage over 62 °F if urged for international adoption; and from a practical point of view it would be no more difficult to change the English commercial standard from 62 °F to 20 °C (68 °F), than to change the metric standards from 0 °C to 16.67 °C (62 °F).

By the 1910s, there really wasn’t a standard reference temperature as much as there were standard reference temperatures for different industries and different countries. I’ll admit the specifics for why this was the case are beyond me. Whatever reasons various industries had at the time for different standard reference temperatures assuredly has a logic that eludes this political scientist. However, the years that followed eventually saw a renewed interest (from the American perspective) in standardizing this measurement and new measurements given ongoing electrification. American industry experts, bureaucrats, and metrologists wanted to standardize more measurements and expand the scope of the BIPM beyond what it had been doing to this point (before 1913). Ideally, it would further standardize international standards to what the United States had been doing through its Bureau of Standards: measuring at 20 °C.

The Bureau of Standards prepared for the upcoming 1927 general conference of the BIPM by shoring up a united message from various industries about the value of 20 °C for standard reference temperature. The French position at this time seemed to concede defeat on 0 °C but wanted a bit more of a convoluted approach to thermal correction than anyone else would accept. The American position (p. 10) was “absolutely not” and the German position was, paraphrased, “hell no.” Whether the latter’s opposition was a function of the ridiculousness of the proposal or some animosity about the fallout of the first world war is not something I feel I can answer.

Meanwhile, the British were still advocating for 62 °F, but found an appeal to Fahrenheit a tough sell. To insert a Swede into this conversation, Carl Edvard Johansson had commanded a lot of intellectual currency to this point—especially in the United States—with his gauge blocks. He argued that his increasingly popular gauge blocks were more durable at 20 °C than they were at 62 °F, at which point body heat exerts a stronger influence on the performance of the gauges. Further, standardizing between Celsius and Fahrenheit was easier at 20 °C than it was at 62 °F. 20 (Celsius) = 68 (Fahrenheit). 62 (Fahrenheit) = ~16.67 (Celsius). If you’re going to standardize, just do what the Americans are doing.

Thus, what was a massive fight at earlier meetings of the BIPM and correspondence on this issue was settled with a voice vote in 1931. The standard reference temperature for industrial measurements became 20 °C. In what I think is the niftiest epilogue to this story, this 1931 voice vote on standard reference temperature has the distinction of being the very first international standard introduced by the International Organization for Standardization. That’s right; it’s ISO 1. People in my field might recognize ISO 3166 for country codes. You might have seen various ISO standards, like ISO 8859 for character encoding. ISO 8601 largely shapes how you see dates and time. None of those are the first post-war international standard. Instead standard reference temperature is ISO 1, an example of the kind of global governance of mundane things done through a non-governmental organization of domestic standards agencies.

The So-Called “-isms” and the Global Governance of Standard Reference Temperature

Students in my field are induced to think of things through the so-called “-isms”. I wish they wouldn’t? No matter, it’s how they’re induced to think and it’s how they’re inclined to think. You can tell an international relations story about this through these various -isms. Not that you should, but you could.

“Realism”

You know how I think. These people are clowns that have nothing to tell you about a question you should care to ask. Carr, Mearsheimer, Morgenthau, Walt, and Waltz would have no real explanation for this story, nor any capacity to care. They’re not particularly capable of explaining the things they like to talk about, let alone things that involve coefficients of thermal expansion, atmospheric pressure, and thermometry. That said, here are the things they would assuredly like to talk about with respect to this.

Realists generally start from an orientation toward the world as one of conflict, and not cooperation. The impetus for an intergovernmental organization like BIPM might have been to harmonize measurements in order to cooperate, but it fell to inherent dysfunction even on what could be dismissed as a “low politics” issue.2 How “tragic” is that, from a realist position, that an IGO on such a “low politics” issue could fall to such dysfunction? It would make sense if you like to talk about the “false promise” of IGOs.

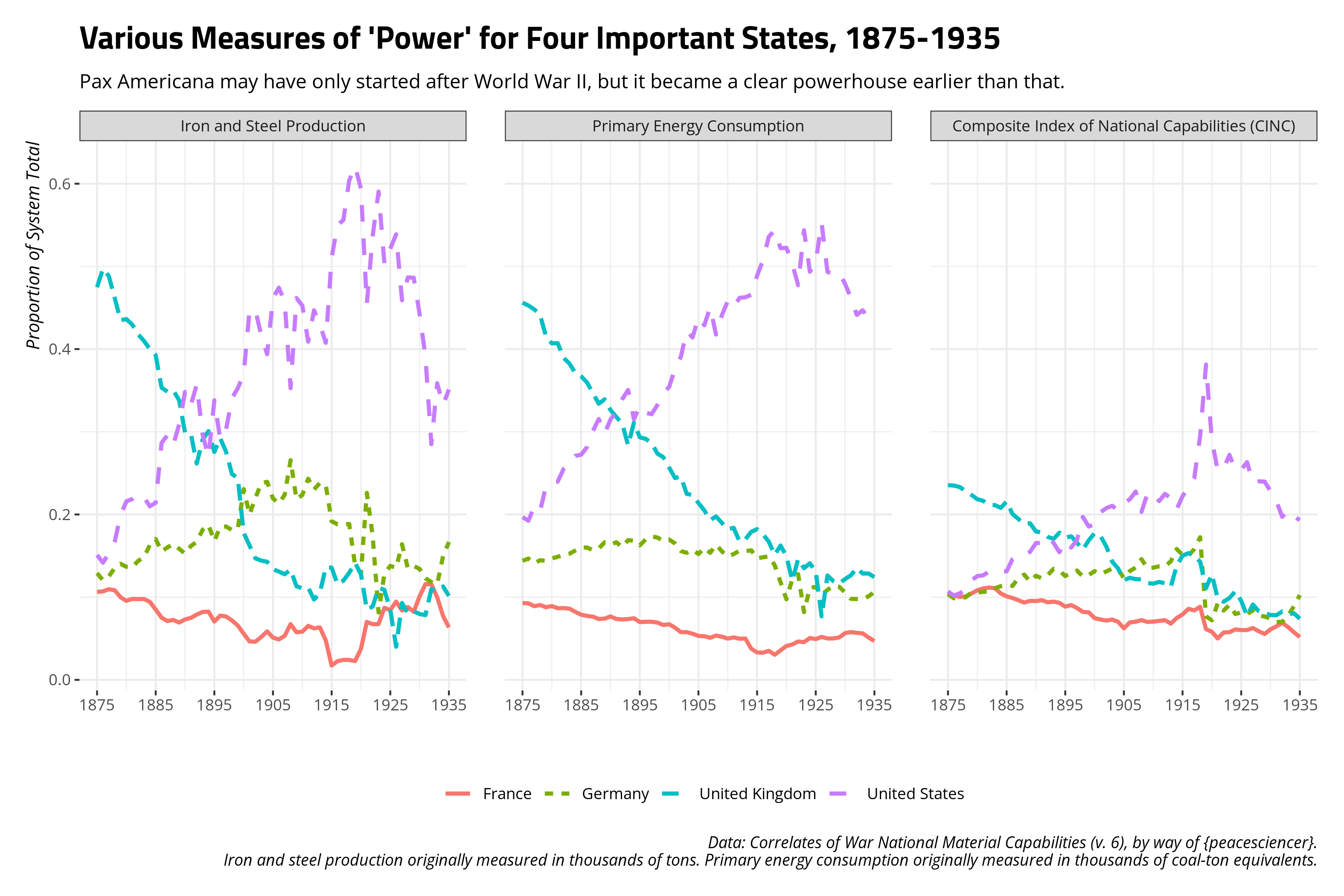

Unsurprisingly, war pervades why this dysfunction emerged and, arguably, serves as the backdrop against which it was ultimately resolved. Great power war put meetings of the BIPM on hiatus. Countries had their own national standards to which they needed to adhere for manufacturing and the war effort. Harmonizing or changing practices would have been an inefficient use of energy at this time, especially when national security is at stake. The end of the first world war (prior to the 1927 and 1931 meetings) and certainly the end of the second world war (prior to ISO 1) definitely accelerated the ascent of the United States as arguably the most powerful country on the planet. It’s not terribly surprising that the U.S. (from this perspective) threw enough weight around to resolve this issue. Take a look at these assorted measures of “power” from the Correlates of War project. I’m standardizing iron and steel production and primary energy consumption to be proportional to the system total in a given year.

cow_nmc %>%

mutate(sumirst = sum(irst, na.rm=T),

sumpec = sum(pec, na.rm=T),

.by = year) %>%

filter(ccode %in% c(2, 200, 220, 255)) %>%

filter(between(year, 1875, 1935)) %>%

mutate(pirst = irst/sumirst,

ppec = pec/sumpec) %>%

select(ccode, year, pirst, ppec, cinc) %>%

gather(var, val, -ccode, -year) %>%

mutate(country = countrycode::countrycode(ccode, "cown", "country.name")) %>%

mutate(var = case_when(

var == "pirst" ~ "Iron and Steel Production",

var == "ppec" ~ "Primary Energy Consumption",

var == "cinc" ~ "Composite Index of National Capabilities (CINC)"

)) %>%

mutate(var = fct_inorder(var)) %>%

ggplot(., aes(year, val, color = country, linetype = country)) +

facet_wrap(~var) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1.1) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(1875, 1935, by = 10)) +

labs(x = "", color = "", linetype = "", y = "Proportion of System Total",

title = "Various Measures of 'Power' for Four Important States, 1875-1935",

subtitle = "Pax Americana may have only started after World War II, but it became a clear powerhouse earlier than that.",

caption = "Data: Correlates of War National Material Capabilities (v. 6), by way of {peacesciencer}.

Iron and steel production originally measured in thousands of tons. Primary energy consumption originally measured in thousands of coal-ton equivalents.")

Perhaps realists don’t care about standard reference temperature and what that means for the history of the meter, but they did co-opt hegemonic stability theory to be one of their things. The U.S. had weight to throw around after the first world war, and used it accordingly.

At least from this perspective, if you had to talk about it. It’s still asking a lot for “realism” to have anything to say here. It’s primarily interested in great power war, not the bureaucratic minutiae of IGOs and fights over where the temperature dial should be to measure things.

“Liberalism”

It’s tough to say what “liberalism” is in international relations. I know I have a PhD in this, but I’m often confused to what “liberalism” is. No matter, I think this is generally what students get on “liberalism”, at least as I would encourage them to see it.

Where so-called “realism” conceptualizes an inherently conflictual system of sovereign states, so-called “liberalism” conceptualizes an international system of more than just sovereign states that is governed as much (or more) by its transactions as its conflict. A narrow focus on state-to-state violence betrays the full scope of international relations. Truly, anything spanning borders is “international” and coordination on measurements and standard reference temperature is “relations” of a kind. A realist might not care about this, but could bullshit you something if pressed. However, a so-called “liberal” would see a lot to like here given how they view the world.

For one, read Doiron’s article and tell me if you recognize any of those names. Be honest, too. If you’re a nerd or versed in the history of Swedish contributions to science, you might recognize Carl Edvard Johansson. However, he’s not a head of state, a defense minister, or a foreign minister. He was an inventor and scientist working for the Ford Motor Company at this time. You might recognize Herbert Hoover, if you’re an American. He would be president soon in this story, but notice he wasn’t. He was the Secretary of Commerce at this point in the story. Realists famously blackbox the state and might make an occasional reference to a top-level diplomat or the state leader, neither of which fit Herbert Hoover in his role in the American government at this point.

Instead, you’re seeing a bunch of actors in a bunch of roles you don’t know about, doing things on an international scale that would’ve shaped your life you were alive at this point. You’re seeing somewhat faceless bureaucrats working in domestic standards agencies like the American Bureau of Standards or its British equivalent. You’re reading about nameless, faceless experts in the BIPM and the authority vested in its secretariat to tell American bureaucrats to pound sand. Go look at Doiron’s list of actors comprising the U.S. industry consensus on p. 8 of its article. None of those consist of the Department of War in the United States.

The familiar kind of actors permitted entry into a so-called “realist” story are nowhere to be seen here. There is no Woodrow Wilson or Robert Lansing. There is no Kaiser Wilhelm or Arthur Zimmermann. There is no David Lloyd George or Sir Edward Grey. There is no Raymond Poincaré or Théophile Delcassé. No one in that kind of position would have that kind of expertise. Thus, they outsource something important-but-obtuse like this to domestic non-state actors to figure it out. You wouldn’t get that in “realism”, but you’re going to get a better picture of it in “liberalism”. Indeed, I largely glossed over how much of this big ol’ snafu is a function of American domestic politics. This started because American bureaucrats and metrologists needed to satisfy legal requirements imposed by Congress.

“Constructivism”

This is a challenge. Mr. Constructivism himself would say “constructivism is not a theory of international politics.”. That’s good as contextualization for what it ultimately is. Constructivism is primarily rooted in the sociology of knowledge, and is foremost interested in the ideational forces that construct the world and give it its meaning.

There are several things here that would work well with a constructivist approach to understanding international relations, broadly understood. Notice there is a great deal of “learning” here. Yes, there is actual technical learning as actors at this time better hone their measurements. However, there is also active learning and an appeal to “experts” to “teach” and “inform.” Carl Edvard Johansson played an important role as a kind of educator informing stakeholders why 20 °C is a better reference temperature in relation to his gauge blocks. There is important teaching going on as the United States sent a battery of industry representatives to persuade other voting members of the BIPM of the “rightness” of its position. There needed to be active educating of the voting members of the BIPM why the French position at the 1931 general conference was a non-starter. Constructivism, as it’s done in international relations, isn’t too far afield from the academic study of education and learning. There is educating and there is persuasion happening in this story, often done by people with certain roles and identities.

Admittedly, this kind of framework isn’t my forté. But you can flesh this out more if you had the spoons for it. The meter is, after all, an interesting social construction of the fraction of a line passing through Paris. We definitely construct the world around us through various means, even if the original idea is that the meter is based on “natural phenomena.”

Conclusion

I wrote this to flesh out something that is a part of a lecture I have to give every semester. The academic interest in global governance concerns some major questions about the movement of people, their basic human dignity, and the climate that they all share. However, this academic interest in some of our most salient and urgent questions comes with an appreciation of how this manifests in some mundane ways we all take for granted. None of us may care so much for the nitty gritty details of what a meter is, or the conditions for which (historically) something was a meter long. But that doesn’t preclude the meter from a conversation of global governance. It most certainly is part of global governance—arguably one of the earliest avenues of global governance. It just means we’re disinclined to think about it and miss some interesting international politics around the conditions for which something historically was a meter long.

There is an important technical and scientific issue underpinning the fight about standard reference temperature, none of which are necessarily political. Thermal expansion is effectively a natural phenomena for which a “social construction” of it would be kind of silly. Further, measuring temperature was an uncertain enterprise around this time, beyond some temperatures that were known with relatively more precision. No matter, even this phenomena had an interesting political fight about what was an appropriate course of action. If you know where to look, or how to look, you’ll find these interesting stories.

You could further contextualize these stories around the familiar “-isms” that have currency in an intro-level international relations track. Not that you should, but you could. I would ask for a bit more by way of explanation for how anarchy (a constant) can explain varying attitudes about standard reference temperature, even if great power war is a clear backdrop to this debate. I would ask for a bit more clarification about the underlying domestic politics motivating the U.S. position and French position, even if you could clearly see the kind of endowment advantage and authority that the BIPM had early into this debate. I would further ask why you’re bringing so-called “constructivism” into this in the first place, even if that particular “-ism” has a unique position as being an offshoot of the sociology of knowledge relative to other paradigms in international relations. I might ask that you theorize the political more than any of these particular “-isms” are willing to do as basic orientations toward international relations.

No matter, anything spanning borders is “international relations”. Yes, even—and especially—standard reference temperature. It’s a cool-as-hell epilogue that it’s ISO 1 if you’re interested in global governance.

-

For the sake of presentation, I will pass over the formalization of uncertainty that went into this bar-based measurement in order to better tell the political story I care about. Measurement of the bar in question included some a measure of uncertainty that, importantly, was subject to surface temperature. Perhaps it’s no surprise that the modern definition of meter anchors to time, not temperature. Time is the most precise thing we can measure. ↩

-

To the best of my knowledge, we have Stanley Hoffmann to blame for this distinction that has since infected how we teach international relations to students. He may have used it before his 1966 publication in Daedalus, though that is the first usage of the terms for which I’m aware. Hoffmann’s treatment of “high politics” and “low politics” has more contours than later invocations of these terms, but it should irk curious students all the same to use these terms in the context of a proposed explanation (“explanation”) as means to dismiss the importance of a question. Like, what even is that… ↩

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.