NATO Countries Spend Just Fine on Defense, and Other Observations

I just got my morning coffee and finished my morning workout. Let’s see what’s in the news today and…

We have a MASSIVE trade deficit with Germany, plus they pay FAR LESS than they should on NATO & military. Very bad for U.S. This will change

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 30, 2017

…oh god. Okay, how many times do we have to tell him that Germany, as European Union member, doesn’t do bilateral trade deals and working up a fit about bilateral trade deficits—a fool’s errand in and of itself—won’t lead to actionable adjustments in Germany?

Beyond that, Trump’s comment here, gleefully reiterated on Fox News (see here and here) suggests a fundamental misunderstanding about what NATO defense spending entails and just how problematic it is. I thought it would be useful to write about it and play with some data toward that end.

I should note, with tongue-in-cheek indictment of Fox News and the President of the United States, that what follows is basically just one lecture in one class in any class I teach on intergovernmental organizations, is heavily derived from de Nevers’ (2007) article on NATO in the “War on Terror” era. It’s not the end-all-be-all of NATO scholarship but it’s a great place to start and International Security could probably ungate it for a while for a general audience.

What Does NATO Do?

My worry is that, as much as people in my field love NATO and regard it is as one of the most successful international institutions ever, most Americans may not know much about NATO. After all, most Americans are inattentive about politics. Heck, more than half routinely don’t know who the Speaker of the House is. One of the “failures” of NATO’s overall success for U.S. security interests is that we as Americans don’t have to think much about it. Our longest-running public opinion polls (e.g. American National Election Survey, General Social Survey) don’t ask about NATO. Thus, inattentive voters may fall prey to priming effects from party elites, further partisanship’s effect as a hell of a drug and the strongest force in the universe.

The long and short of NATO is it is a multilateral intergovernmental organization, and also an alliance, that coordinates mutual security policies among its members. Its origins are clearly post-World War II and not just Cold War concerns. Effectively, the North Atlantic Treaty signed in Washington in 1949 subsumed the Treaty of Brussels from the previous year. Both differ in that Western Europe still regarded Germany, occupied at the time, as its gravest security threat. Then it became apparent that the Soviet Union, and not Germany, was the greatest security threat to Europe. This resulted in the expansion of what was originally a Western European security pact into a North Atlantic (i.e. Canada and United States) security pact that expanded just six years later to also include Greece and Turkey (both in 1952), and the Federal Republic of Germany (1955). Greece and Turkey were no friends to each other, and never have been, but Greece had just ended a civil war against communist insurgents and Russia, which had fought against Turkey at least 11 times in war, preferred the Turkish Straits in Bosphorus and the Dardanelles as its access to the Mediterannean. The addition of (West) Germany—whose notoriety for Western European signatories like Belgium, Netherlands, and France needs no introduction—should serve as a strong signal about the severity of the Soviet threat.

The happy epilogue to the Cold War was the eventual removal of the Berlin Wall, the physical manifestation of the Soviet expansionary threat. Since then, NATO expanded in the late 1990s and early 2000s to include several former Warsaw Pact countries that still (rightly) regarded Russia as its biggest security threat. The nature of the Russian threat may have been less direct and obvious than the Soviet threat, which has resulted in some speculation about NATO’s trajectory. Prior to the Russian invasion of Georgia, the United States wanted to repurpose NATO to serve more of its concerns for the War on Terror. However, European allies in NATO (rightly) feared “entrapment” in the Middle East when the U.S. almost “abandoned” it on the Yugoslavia issue that concerned European allies more. There were still considerable misgivings among NATO members about the U.S. as a result of these “entrapment” and “abandonment” concerns. Obama papered over a fair bit of it, until the end of his time in office. Trump has only magnified these concerns.

What is That “2% of GDP” Thing?

The “2% of GDP” thing for which you hear Trump making a fuss concerns a mutual benchmark that NATO set for its members. To mitigate some of the problem of burden-sharing, which falls disproportionately on the United States, NATO wants its members to commit 2% of its gross domestic product (GDP) to defense spending. This used to be 3% of GDP during the Cold War, but that benchmark adjusted downward as a result of the happy conclusion of the Cold War.

If you believe Fox News, almost allies are failing on this benchmark.

2016 defense contribution to NATO - share of GDP. pic.twitter.com/9DcWFZcUDv

— Fox News (@FoxNews) May 27, 2017

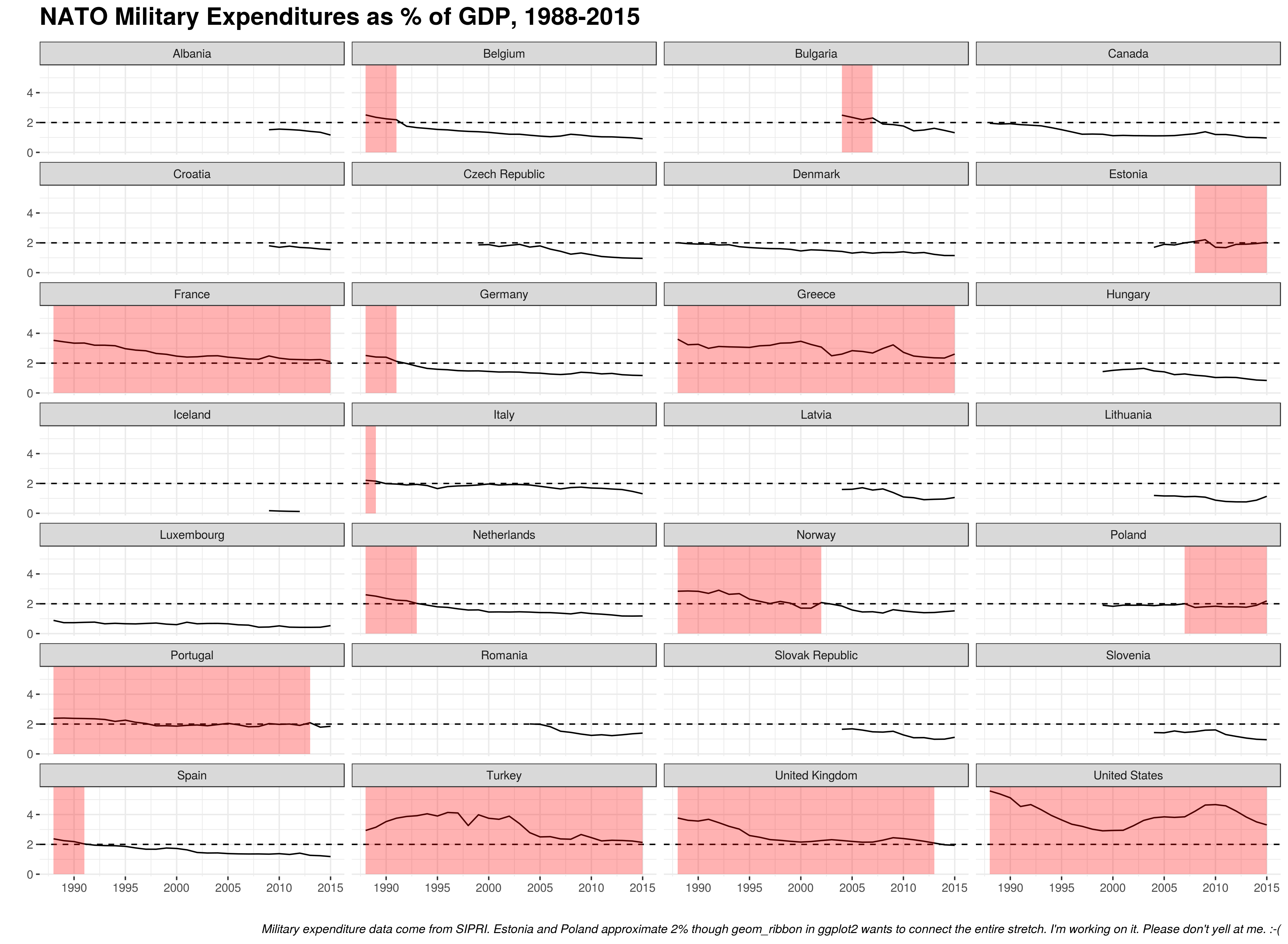

Here’s a more informative graph using military expenditure data from SIPRI, as gathered on the World Bank.

Here’s a more honest interpretation that you won’t get from Trump or the Fox News treatment. Most allies are making honest efforts to satisfy this threshold. Only six NATO members (United States, France, Poland, Greece, Estonia, and Turkey) met this treshold in 2015 but many more are in the ballpark (e.g. Portugal, United Kingdom, Croatia, Norway). If your eye is drawn to Iceland, recall: Iceland is an original signatory to the North Atlantic Treaty and never entertained any idea of seriously spending as much on defense. Iceland effectively volunteered itself as a port in the Atlantic in the worst-case scenario.

Should We Care about that “2% of GDP” Benchmark?

My hot take: no.

The problem is both Trump and Fox News are confusing a benchmark for a hard-and-fast rule. In Trump parlance, both confuse a NATO benchmark for country club dues. That’s not how this works. That’s not how any of this works.

Recall, that GDP is a moving target. We uncritically treat it as a measure of national wealth but it formally measures the sum of the gross values added of all resident and institutional units engaged in production (plus any taxes, and minus any subsidies). You might not appreciate that government expenditures are included in the gross domestic product. It’s the G in Y = C + I + G + (X - M) (where Y is GDP). Thus a country that increases its military spending (i.e. the numerator) also increases its gross domestic product (i.e. the denominator).

You should also appreciate that countries draw budgets prior to the referent year for GDP calculation. Thus, the target moves further.

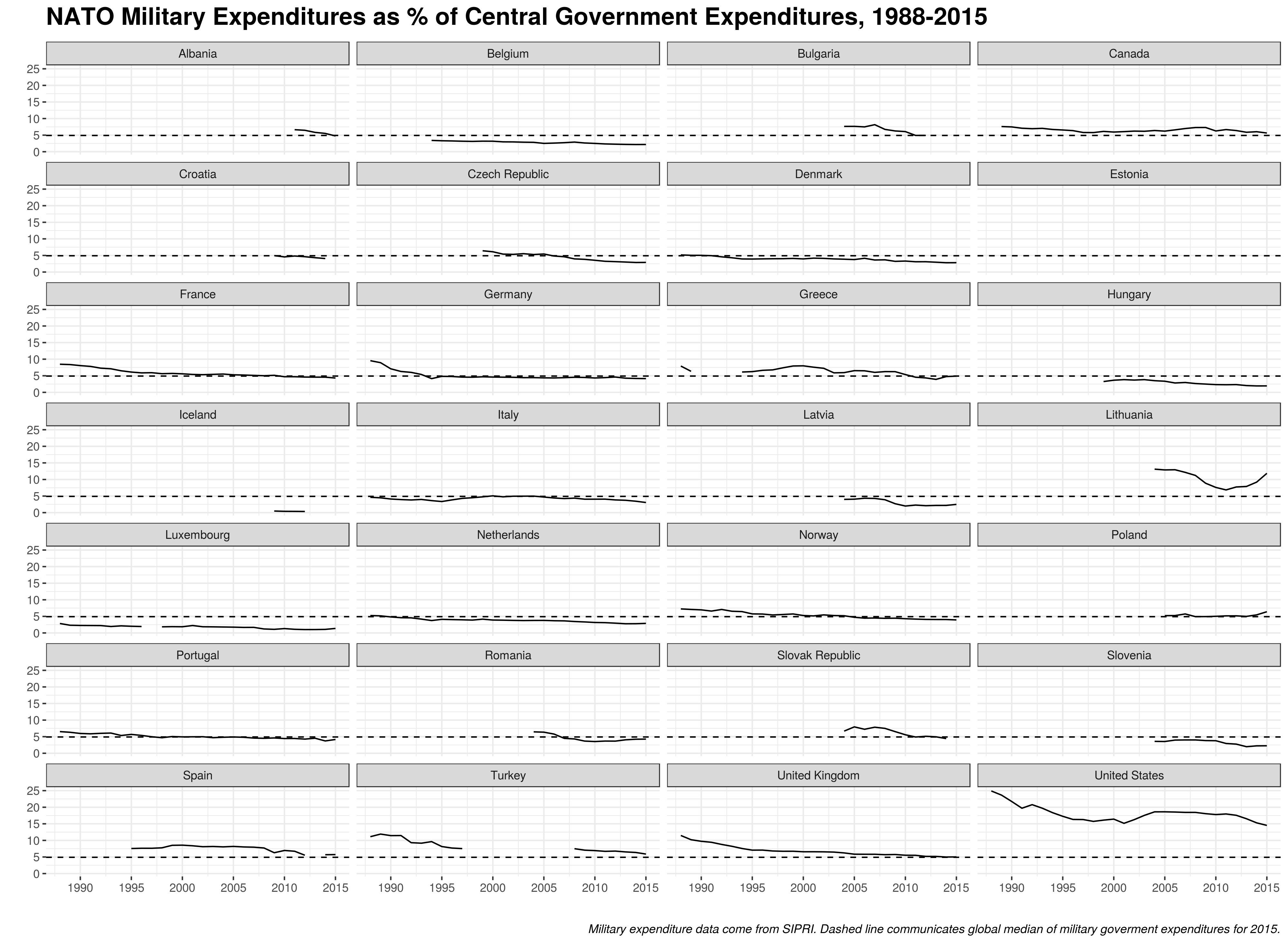

A more informative metric might be military expenditures as a percentage of overall government expenditures. Here, I gather data from the same source and chart changes in military spending as a percentage of central government expenditures against the global median for 2015 (i.e. 4.90%). Observe that seven countries are above the 2015 median, even Canada and Spain. These are two countries Fox News cherry-picked as “free-riding” and are two countries that dedicate a considerable portion of their budget to defense even if their allocation is not nearly as exorbitant as what the United States spends.

Here’s another hot take: European ally free-riding on the U.S. security umbrella is, to borrow programming parlance, a design feature and not a bug. The real lesson learned from World War II is arms races coinciding with economic nationalist agendas in Europe led (and would lead again) to the deadliest wars. The United States has spent considerable effort allowing the allies to spend less on defense and integrate its economies more because both policy changes after World War II have been conducive to peace. The United States has demonstrated that it is peculiar in its ability to spend exorbitant amounts of money on defense without going bankrupt. Further, Europe is its No. 1 most important security commitment. Allowing Europe to spend less on defense has been unequivocally good for the United States (and Europe).

Further, look at some of the countries that are meeting the 2% benchmark or spend above the global median on defense as part of its central government expenditures. You’ll see countries like Estonia, Lithuania and Poland stand out. Compare those observations with Trump’s tweet berating Germany. The request from Trump effectively amounts for a demand for Germany to spend more money on defense against its major security threat (Russia) with whom the U.S. president is now “besties.”

Every president asks NATO allies to invest more in defense. However, the current track from the U.S. president, if successful, would lead to a massive investment in defense spending because it doubts the credible commitment of the United States to its security. This would undo more than 70 years of peace in Western Europe that was based on the good intentions and credible commitment of the U.S. as hegemon.

So What Should We Chide NATO Members About?

There are and have been several more important things to implore NATO allies to do beyond the 2% benchmark.

For one, did you notice that Greece and Turkey are the two countries that have reliably been above the 2% benchmark in the first graph? The problem for the United States is both invest considerable parts of their budget and GDP on defense and concentrate them in manpower against each other. Greece is even the most militarized country in NATO where militarization is measured as the number of military personnel over the total population. That Greece even meets this threshold notwithstanding its major economic crises should tell you that Greek defense spending isn’t money wisely spent or necessarily tailored toward the good of NATO. It’s still derivative of Turkey and the multiple issues Greece and Turkey still have with each other.

The United States has also implored its NATO allies to transform their militaries to meet modern security threats (i.e. the War on Terror). This has taken on multiple forms, including investments in counterterrorism capabilities and the development of “niche” capabilities that would complement what the U.S. does well and would avoid overlap. Here, there is an unmistakable element of American hypocrisy. The United States was the most vocal advocate for NATO’s expansion east of Germany even though it was obvious then (and still is now) that recent additions to NATO do not meet NATO’s military capability standards. They are still worthwhile and important security obligations for the United States, but both Clinton and Bush knew what they were getting when they pushed for eastward expansion of NATO.

Further, U.S. pleas to invest more in counterintelligence both ring hollow and again reek of hypocrisy and self-inflicted wounds. The U.S. spends north of $50-billion on intelligence operations. By comparison, that’s effectively 100% of France’s overall military budget and more than what the United Kingdom spends on defense overall. Both countries are No. 2 and No. 3 in NATO defense spending and have the No. 6 and No. 7 biggest military budgets in the world.

This results in the United States ultimately producing most of the actionable intelligence it wants. What intelligence it doesn’t produce it subsequently blabs out loud (see: Israel, Manchester), further hurting its efforts.

If I were president, my bigger concerns in NATO would be about smoothing relations between Greece and Turkey (especially as Erdogan seems to fancy himself as the next great “sultan”, to Greece’s chagrin), better integrating and developing counterterror operations and intelligence sharing, and—as I cannot believe I have to say this—reiterating that Article V is law and the U.S. takes seriously any threat to peace in Europe. Europe is the most important security obligation for the United States.

The “2% of GDP” metric would not seriously enter the conversation, nor should it.

Code and Footnotes

Code is available as a Gist on my Github.

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.