The Kids May Be All Right: Millennials and Democratic Support

- This Arizona woman leads a chant as voting-rights demonstrators stage a sit-in at the Capitol. She's not part of the problem. (AP Photo / J. Scott Applewhite)

Liberal democracy is in a rough spot right now. I won’t challenge that. I will, however, challenge a monocausal explanation that democracy is deconsolidating because of the young’ns. These are the familiar “Millennials”, people born after 1981. They are convenient targets for pundits and even some academics because of their perceived lack of support for democracy among other alleged shortcomings (i.e. the damn music, skateboarding on the sidewalk, other chicanery).

In the interest of full disclosure, I am a Millennial (older one at that) who teaches younger Millennials as part of my professional obligations. I at once see their promise and their shortcomings.1 I don’t think blaming them for the lack of democratic support is appropriate. Instead, the evidence we see that is consistent with a lack of support for democracy among American youth is either 1) a misrepresentation of the data and/or 2) possibly a “heaping” phenomenon we see in survey data in which respondents who don’t know how to answer a question use some type of satisficing heuristic to arrive at a familiar number or place themselves in the middle of the set of available answers.

My interest here is largely the United States, so I will focus on the American case.

Before going any further, I will editorialize that blaming the Millennials for Trump is demonstrably wrong. His election victory is the strongest event to date about how democracy is hanging in the balance so this point is worth reiterating. If the vote were left entirely to Millennials—disenfranchising all Gen Xers, the Boomers, and the remaining Greatest/Silent Generation folk—Trump would have been routed. It would not have been close. The Boomers collectively gifted Trump to the younger generation both with their votes and their outsized view of what their childhood was like. Don’t pin that on the kids.

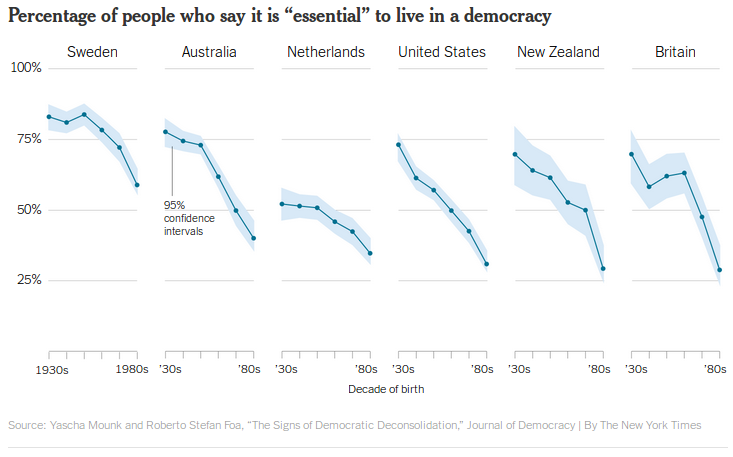

My hunch is everyone has seen the graph to the right. The New York Times published it. It purports to show a steep decline in support for democracy in six enduring democracies. The U.S. figure is important here since it implies only Britain and New Zealand surpass it in terms of Millennials who do not think it essential to live in a democracy. It also strongly implies that less than half of Millennials don’t think it essential.

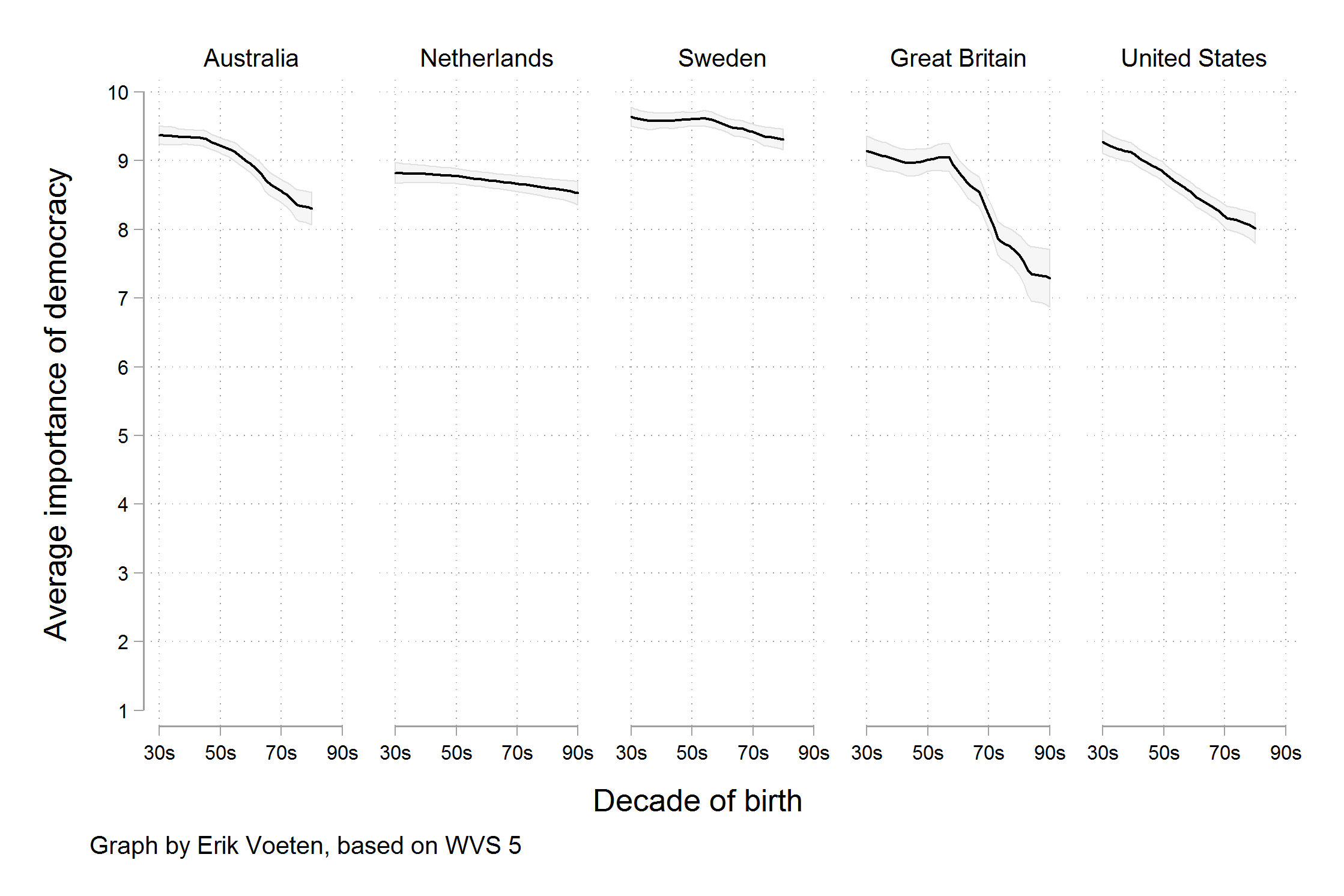

Erik Voeten noted this is a highly selective scaling of this particular variable from World Values Survey. Basically, the authors of the study the New York Times cites select on the full 10s on the 1-10 variable from World Values Survey. Show the full scale and average across it and the decline in support for democracy’s essentiality does not look as stark. This is a good illustration of how to be careful in reading a decline or negative relationship. A negative relationship here just suggests that younger citizens are less likely to think of democracy as “more essential” relative to older citizens. It does not mean that younger citizens think of democracy as “not essential.”

It’s an important nuance you’d learn in my quantitative methods class. Put another way, don’t misconstrue “a negative relationship between x (age) and y (importance of democracy)” with “x (age) makes y (importance of democracy) negative.”

Voeten has a working paper, summarized here on The Monkey Cage, that expresses further skepticism about the “democratic deconsolidation” argument that Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk argue in Journal of Democracy. You should read it, but I’ll offer one interpretation that Voeten does not. I don’t think Millennials are necessarily abandoning democracy; I just don’t think they know how to answer the questions that survey researchers give them.

Consider that Voeten’s working paper looks at the familiar battery of political systems questions that I use in my forthcoming article in Political Behavior. These questions—gauging support for rule of government by 1) a strong leader who can rule by discretion, 2) the army, 3) “experts” (i.e. unelected technocracy), and 4) democracy—are all on a four-part scale of “very good”, “fairly good”, “fairly bad”, or “very bad.” Voeten’s preliminary results find effectively no movement over time or across generations, which would scquare well with the mixed support for the age-support for democracy relationship I incidentally evaluate in my Political Behavior article.

Yet, there is that small movement he notes in the question that Foa and Mounk use and blow out of proportion for Journal of Democracy and New York Times. Younger folk are more likely to score lower on the 10-part “importance of democracy” than citizens who are older. I found the same thing in the regression context for an analysis I did in May on the same data.

I’m not convinced this is necessarily evidence of democratic deconsolidation among Millennials. I’m instead wondering if it’s “heaping” that we can discern because this item has 10 available repsonses whereas the other World Values Survey items just have four possible responses. Younger citizens who don’t know how to respond to this question are putting themselves in the middle, which is just one of several forms of “heaping” that respondents do when they need a shortcut to answer a question for which they don’t know how to respond.

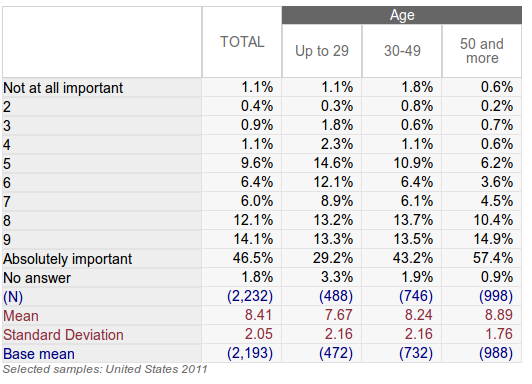

The evidence I have for it is largely circumstantial, but let’s look first at a cross-tabulation of the responses for the sixth wave of World Values Survey data for the United States. Notice the proportion of respondents who did not answer this question is quite small. When asked this question, only 39 of the 2,232 respondents chose not to disclose an answer for one reason or the other. Contrast this with the 72 respondents who gave no answer to the four-part “having a democratic political system” item in the same survey.

Your eye will instinctively gravitate to the plummet of responses for “absolutely important”, which constitutes a magnitude drop going from the 50-and-more crowd to the up-to-29 group (i.e. the Millennials). However, look at the percentage of cases at or near the “not at all important” response. The differences are negligible. Six (yes, just six) of the 998 respondents in the 50-and-more group thought having a democracy is “not at all important” compared to the five (yes, just five) of the 488 Millennials who answre that democracy is “not at all important.” Let this underscore the peril of reading between tea leaves for subpopulations in surveys.

The proportion of responses at “5” intrigues me. The proportion of responses at “5” for the Millennials is 14.6%, which drops to 10.9% for the 30-49 group and later to 6.2% for the 50-and-more. This is consistent with one implication for those that study “heaping” in survey responses. Those that do not know how to answer a question and rely on a shortcut tend to gravitate toward 1) the middle and 2) numbers divisible by 5 or 10.

There’s a similar phenomenon in the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) data for the United States. I selected data from the 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014 waves for an item that appears that is roughly similar to the four-item “having a democratic political system” question from World Values Survey. This question, however, is a more familiar Likert item with the following prompt: “Democracy may have problems, but it is better than any other form of government. To what extent do you agree or disagree with that statement?” This is what I call the “Churchill question” given its similarity to Winston Churchill’s famous (however stylized, ex post) quote about democracy. Unlike the World Values Survey version, the respondent answers 1-7 on a scale of agreement. Higher values imply more agreement.

I then created a cross-tab with columns for generations as Pew codes them. Results follow.

| Democracy is better than any other form of government | Greatest/Silent | Boomer | Gen X | Millennial |

| 1 | 1.98% | 2.51% | 3.07% | 2.98% |

| 2 | 0.53% | 1.48% |

2.49% | 3.78% |

| 3 | 1.72% | 3.42% | 6.77% |

6.84% |

| 4 | 4.88% | 10.09% | 16.99% | 20.53% |

| 5 | 10.29% | 13.88% | 17.37% |

18.84% |

| 6 | 24.67% | 23.89% | 22.41% | 19.00% |

| 7 | 55.94% | 44.73% | 30.91% | 28.02% |

| Sum | 100% | 100% |

100% | 100% |

There’s evidence here consistent with the democratic deconsolidation argument among Millennials. The percentage of responses most in agreement with the prompt shrinks considerably going from the Greatest/Silent generation to the Millennials. However, the percentage change for the 1s (most in disagreement) doesn’t move much. Though there are more observations (and more Millennials) in the four rounds of LAPOP data than the sixth wave of World Values Survey data for the United States, the caveat applies that we’re still talking about a small subpopulation. Only 161 of the 5,994 respondents here said they were most in disagreement with the prompt. Of those 161 respondents, 37 were Millennials.

There’s also a lot of heaping in the middle, which happens to be at 4 in the seven-item response. Notice the percentage points increase at 4 of 4.88% (for the Greatest/Silent folk) to 20.53% for the Millennials. That’s a magnitude percentage point change for one value across the range of x (here: generations) that’s rivaled only by the decrease of 7s. This is consistent with democratic deconsolidation; it’s also consistent with heaping.

Why we observe this heaping for Millennials is worth exploring, but I won’t have all the answers right now. I imagine a lot of this will be the Cold War. Millennials largely came of age without the Cold War and may not have had the same kind of cues about the importance of democracy as Boomers, even Gen Xers. They’re not as conditioned to give the maximum response to these kind of questions. Millennials are also younger and lack political experience and sophistication (relative to generational counterparts) to answer this question. Democratic satisfaction does not appear to be a correlate here. There is no discernible difference I could find among generations and their satisfaction with democracy, at least using the LAPOP data.

Consider everything here tentative. I felt like writing it as a diversion from grading. I might invest more energies over the holidays into a short paper on the topic if I were convinced I could parlay it into something in which a journal editor might be interested. For the meantime, be mindful of blaming the Millennials for democratic deconsolidation. The kids may be all right. They’re certainly not all wrong.

-

i.e. I’m writing this instead of grading papers and exams 😛 ↩

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.