Stephen A. Smith and International Relations Scholarship

- I used to be proficient at Photoshop in a past life. It's just easier for ChatGPT to do this for me instead (because it did).

Are you explaining it or are you just talking about it?

This is a question I routinely raise on student papers in my department in a curriculum that is wedded to the so-called “isms”. It’s pervasive here. Students think firmly inside those boxes. I don’t even want them thinking outside the box. I want them throwing the box away (or recycling it, whatever complies with local environmental regulations).

If I’m asking you to explain something or make sense of something, I want you to actually do it. If I’m asking you a question, it’s because I want an answer. Answer the question. I don’t want you restating it, because restating the question as an answer is begging it. I don’t want you answering a question with an answer to a related or unrelated question I did not ask. Answer the question that I asked. If I want an explanation, give it. If you’re not explaining something to me, you’re just talking about it. I don’t want you just talking about it; anyone can do that. I want you explaining it.

My go-to example for students at Stockholm University concerns a guy that maybe one or two people in the room have heard about. Several have been to the United States and a few (always the men) are aware of ESPN sports programming. No matter, this fellow is named Stephen A. Smith. He’s a “sports television personality” (we’ll go with that) who has become famous and wealthy for doing bombastic things with no real informational value. Shticks feature prominently into his repertoire, and one of his shticks is hating the Dallas Cowboys.

Observe, from this video six years ago with respect to the 2018-19 NFL season. Therein, the Dallas Cowboys finished 10-6, beat the Seattle Seahawks in the wild card game, but lost to the eventual Super Bowl runner-up Los Angeles Rams in the next game.

You may or may not have found that entertaining. You certainly didn’t find it informative of anything you may have cared about.

I don’t know or care to know why Stephen A. Smith detests the Dallas Cowboys, but let’s dive a bit into this. The 2024 Dallas Cowboys finished 7-10, 3rd in the division, and did not make the playoffs. I’m sure Stephen A. Smith enjoyed talking about this, but anyone can do that if they’re interested. How do we explain this disappointing season after a 2023 season in which Dallas finished 12-5 and won the division? To do that, you’d have to do more than just talk about it, or restate the season as disappointing. You’d have to understand a bit about the game itself, or at least try a little bit.

For example, offensive tackle—especially the left “blindside” tackle—is a premium for pass protection in a pass-heavy game. Tyron Smith, an 8x Pro Bowl tackle, left in the off-season for a final payday with the New York Jets and the Cowboys needed to use their first round draft pick on his replacement. Tyler Guyton, had a disappointing season and arguably played out of position as a left tackle. He was a right tackle, for the most part, at Oklahoma. QB pressures, as a count, increased almost 33% from 2023. Perhaps it was a mistake for the Cowboys to feature Ezekiel Elliott as prominently as they did. Elliott was an amazing player for the Cowboys in his first few years, but injuries and wear and tear have caught up with the nine-year pro. The Cowboys switched defensive coordinators from 2023. Dan Quinn relied on a lot of Cover 3 with man coverage coordinating the Cowboys defense, but complemented it with some Cover 1 and Cover 2 looks. Mike Zimmer, his replacement, dialed down the Cover 1 and Cover 2 looks and placed more emphasis on Cover 3 (which is a base look just about everywhere in the NFL) and Cover 6. Coach what you know, and there’s always a peculiar song and dance making an outside hire to replace a guy who optimized a system in a particular way. However, this change comes after losing 2023 cornerback Stephon Gilmore to the Vikings and playing most of the season without Daron Bland (the other corner). The switch in philosophy may have adversely affected Markquese Bell, who played further outside the proverbial tackle box than he did under Quinn. Bell had a disappointing 2024 season (just six tackles) before a season-ending injury after nine games.

I did not watch any of the NFL in 2024, so I can’t say any of these things with much confidence.1 No matter, I feel I can offer them as at least partial explanations for why the Cowboys had a disappointing 2024 season (ignoring what other opponents, like what division rival and eventual Super Bowl champion Philadelphia Eagles, did to improve from 2023). It required effort. It required understanding basic strategies and logics that coaches employ, and knowing about the game itself. It willfully took something complex and distilled it into some simple parts that get at the essential features of the performance of an NFL team. It required contextualizing injury and attrition. It required understanding how sometimes the talent pool is shallow or mismatched for the philosophy of the coaching staff. I tried to do more than answer a question of why the Cowboys season was so disappointing by restating that it was. I tried to explain it, not just talk about it. Anyone can do the latter, and truly anyone can do that wearing a cowboy hat and being a troll about it. However, you are not informed. Perhaps that’s not the point of the Entertainment and Sports Programming Network (ESPN), but it should leave you wanting more than you got.

I go to this example because there is an entire strand of international relations scholarship that has long-worked on this exact same model. It has never seriously tried to explain (or explain well) the pressing questions of international relations. It’s instead been all too content to just talk about it and offer whatever entertainment that could be derived from this farce as having informational value.

Take Kenneth Waltz, for example. Waltz had some real bangers, like this one (re: anarchy) on p. 232 of Man, The State, and War:

Applied to international politics this becomes, in words previously used to summarize Rousseau, the proposition that wars occur because there is nothing prevent them. Rousseau’s analysis explains the recurrence of war without explaining any given war. He tells us that war may at any moment occur, and he tells us why this is so.

That something could happen is not an argument why it does or does not happen.2 I would say this is an exceptionally lazy argument, except I’d have to qualify it as an argument.3 A la Wagner (2007) and my training in the Correlates of War tradition, just know that we conceptualize war as “severe” subsets of violent confrontations (i.e. not “cola wars”). We operationalize them by fatalities. You can learn more about this here with respect to inter-state conflicts. War may make the state and the state may make war, but “war” has never required sovereign states in order to happen.4 Anarchy, a constant feature of the international system as we may describe it, is clearly not a sufficient condition for war. It’s not necessary for war either. Saying this, as he did, with such conviction belies the nonsense that it is.

Also, take this from Theory of International Politics as the seminal statement of the balance of power thesis (p. 119):

Balance-of-power theory claims to explain a result (the recurrent formation of balances of power), which may or may not accord with the intentions of any of the units whose actions combine to produce that result. To contrive and maintain a balance may be the aim of one or more states, but then again it may not be. According to the theory, balances of power tend to form whether some or all states consciously aim to establish and maintain a balance, or whether some or all states aim for universal domination.

Ignore, for the moment, the omission of agency for states or heads of state in a tradition that goes out of its way to treat humans like they were objects in motion. That’s a disease that is endemic to this tradition, which it states up front as a disability to absolve itself from thinking about anything internal to the state in any detail. But what even is this? What does it mean that something “tends to form”, “which may or may not accord with the intentions of any of the units?” Feel free to read the few pages before it where he assumes a system of independent states and the mechanisms at their disposal to achieve these ends “in more or less sensible ways” (whatever that means). You’re still left with the question of what on earth Waltz is trying to say. What is he trying to say? I’m putting a few words into the mouth of the late Bear Braumoeller (2013, p. 14), but it’s supremely rich that Waltz spends the bulk of his first chapter (second section, especially) complaining that competing theories of international politics to his are so imprecise that hypotheses cannot be stated in ways that would make falsification possible. Waltz is just as imprecise as what he’s criticizing.5

I never met Waltz. He retired before I entered the profession and passed away in 2013. I’ve not encountered many people in my field rolling their eyes at him as if he were a troll like Stephen A. Smith. However, accusing others of making imprecise arguments by making an even louder imprecise argument is something I’d imagine Stephen A. Smith doing if he were on an “Author Meets Critics” panel at ISA. I just can’t be as deferential in the absence of information to John Mearsheimer, though. The mechanism is the same, but louder and more bombabstic. Like Stephen A. Smith, Mearsheimer has a shtick. He has a few of them, actually, and he’s the primary inspiration for the image.6 Let’s start with this opening salvo from “Why the Ukraine Crisis is the West’s Fault” (which, Jesus Christ, that article title).

Putin’s pushback should have come as no surprise. After all, the West had been moving into Russia’s backyard and threatening its core strategic interests, a point Putin made emphatically and repeatedly. Elites in the United States and Europe have been blindsided by events only because they subscribe to a flawed view of international politics. They tend to believe that the logic of realism holds little relevance in the twenty-first century and that Europe can be kept whole and free on the basis of such liberal principles as the rule of law, economic interdependence, and democracy.

But this grand scheme went awry in Ukraine. The crisis there shows that realpolitik remains relevant—and states that ignore it do so at their own peril. U.S. and European leaders blundered in attempting to turn Ukraine into a Western stronghold on Russia’s border. Now that the consequences have been laid bare, it would be an even greater mistake to continue this misbegotten policy.

“Only the U.S. and the West do dipshit things in the name of domestic politics and ideology while poor hapless Russia is simply responding to ironclad laws of nature.” This is not a serious statement. This is a shtick, like Stephen A. Smith in a cowboy hat. It’s a recurring gag. It’s the IR analogue to Andrew Dice Clay’s “nursery rhymes” bit. I would say it’s funnier than Clay’s “Mother Goose” but Clay’s most grotesque and woefully cringe material isn’t a pretense for an ethnic cleansing campaign. If this isn’t supposed to entertain, was it supposed to seriously inform? I would think the answer is an obvious no. It’s not supposed to explain the underlying logic of what the U.S. and Europe have done. It sure as hell doesn’t explain what Russia has done or is doing. It’s designed to get the kind of engagement and recognition like the kind the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs would provide. And they have provided it. On more than one occasion.

Btw, this is pages 2-3 of Tragedy of Great Power Politics.7

There are no status quo powers in the international system, save for the occasional hegemon that wants to maintain its dominating position over potential rivals. Great powers are rarely content with the current distribution of power; on the contrary, they face a constant incentive to change it in their favor. They almost always have revisionist intentions, and they will use force to alter the balance of power if they think it can be done at a reasonable price. At times, the costs and risks of trying to shift the balance of power are too great, forcing great powers to wait for more favorable circumstances. But the desire for more power does not go away, unless a state achieves the ultimate goal of hegemony. Since no state is likely to achieve global hegemony, however, the world is condemned to perpetual great-power competition.

This unrelenting pursuit of power means that great powers are inclined to look for opportunities to alter the distribution of world power in their favor. They will seize these opportunities if they have the necessary capa bility. Simply put, great powers are primed for offense. But not only does a great power seek to gain power at the expense of other states, it also tries to thwart rivals bent on gaining power at its expense. Thus, a great power will defend the balance of power when looming change favors another state, and it will try to undermine the balance when the direction of change is in its own favor.

Mearsheimer is complaining that the United States did what we would expect them to do in the 1990s, under the circumstances. States maximize relative power (p. 163, same book), except when they shouldn’t, for ~ reasons ~. Tom Pepinsky notes how frustrating it is that Mearsheimer is able to effortlessly weave between arguments of what states do and what states should do, often in the same paragraph, and in ways that contradict each other. Frustrating? Yes. But this is the dude wearing Machiavelli’s robe as a greeting. If we’re asking for an explanation, we’re not getting it. If we’re asking for sincerity, that’s on us. He’s content to talk about it, though for what I’m sure is a hefty speaker’s fee. If you want some insight into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I can point you to Olga Chyzh’s commentaries on it. I can point you to the special issue that came out last year in Conflict Management and Peace Science that explored the fundamental bargaining problems that incentivized Russia for war and make an off-ramp difficult to find. Olga’s brilliant and publicly accessible and your university library already paid for access to this special issue (along with the rest of the journal/publisher’s catalog). Even if you find yourself behind The Guardian’s paywall or aren’t at a university with a SAGE or EBSCOhost subscription, you will learn more about the situation at a fraction of the cost. Please contact Raleigh Addington at Chartwell Speakers if you’d like to pay more to learn less, though.

Again, from Tragedy of Great Power Politics (pp. 30-32), where Mearsheimer says he’s proposing an explanation of the behavior in the international system.

The first assumption is that the international system is anarchic, which does not mean that it is chaotic or riven by disorder. It is easy to draw that conclusion, since realism depicts a world characterized by security competition and war… The second assumption is that great powers inherently possess some offensive military capability, which gives them the wherewithal to hurt and possibly destroy each other… The third assumption is that states can never be certain about other states’ intentions. The fourth assumption is that survival is the primary goal of great powers… The fifth assumption is that great powers are rational actors. They are aware of their external environment and they think strategically about how to survive in it.

As emphasized, none of these assumptions alone dictates that great powers as a general rule should behave aggressively toward each other. There is surely the possibility that some state might have hostile intentions, but the only assumption dealing with a specific motive that is common to all states says that their principal objective is to survive, which by itself is a rather harmless goal. Nevertheless, when the five assumptions are married together, they create powerful incentives for great powers to think and act offensively with regard to each other. In particular, three general patterns of behavior result: fear, self-help, and power maximization.

This is a description of the international system masquerading as an explanation of the international system.8 It doesn’t explain the behavior of states in it, but talks about essential assumptions we make about the absence of a global sovereign in a system where the primary units have instruments for harm. Like Waltz’s (1959) appeal to Rousseau, Mearsheimer writes this to imply he’s said something more than he has. It’s a clever writing device to say something with a demonstrative authority to belie the nonsense it is. Talking heads on cable television—like Stephen A. Smith—do this all the time with their delivery of the spoken (if not written) word. The international system has always been anarchic. All states—let alone great powers—possess the capacity for harm toward others (whether it’s horses or nuclear weapons). We can qualify, perhaps, how much weight we want to put on the certainty assumption, but sure, probability is never 0 or 1 in a real world governed by at least a little noise/chance.9 States exist to not go the way of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was conspired out of existence in 1795. Got it. Trivial, but got it. States are rational/strategic actors. Sure, Mearsheimer never belabors what he means by that, and likely did not consult Tsebelis (1989) for caveats, but we’ll worry about those details later. We’ve identified five constants that (near direct quote) “when married together, create powerful incentives for great powers to think and act offensively with regard to each other.” I’ve no idea what that is supposed to mean (i.e. this is more of a word salad than you appreciate after a first reading), but we’ve identified behavior that varies across time and space as functions of five things we believe do not vary. To borrow lingo popular in the drag community, Mearsheimer thinks he ate with that passage and left no crumbs. I’d say there were crumbs but the damn thing fell on the ground and we’re almost 25 years past the five-second rule. The flies already got to it.

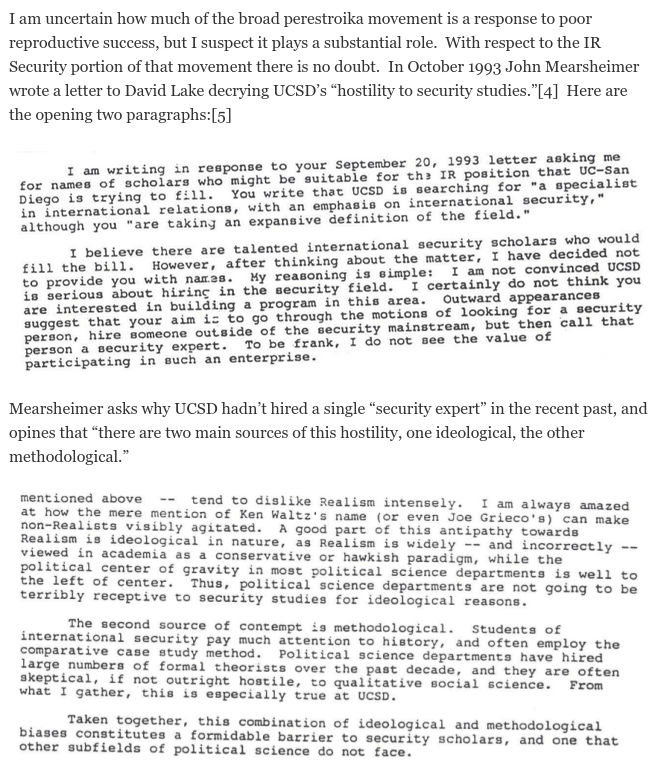

“Such a distinguished professor at a prestigious university can’t simply be a troll” asks the curious reader who did not enter graduate school in the afterglow of the so-called Perestroika movement in the discipline. The discipline leveraging greater clarity and technological sophistication became quite the existential threat to the engagement troll that suddenly finds itself with a diminished platform. No, the engagement trolls still feature prominently in the outlets more accessible to the general public (whether periodicals like Foreign Affairs or cable television networks like CNN). They’re still getting their speaker fees and are getting enough of them to justify paying for an agent as a business expense. They still found ample time to publish complaints about “rigor” in theoretical argumentation before courting the same community to complain about the quantitative folks. The blue hairs doing this are fine, but their graduate students found it tough-sledding to run back the adviser’s playbook in an academic climate more interested in explanations than conjecture. I’m going to link to Will Moore’s 2015 blog post on this and implore you to read it in its entirety if you haven’t. I came for the stuff I already knew and figured out pretty quickly in graduate school about the Mearsheimer/Walt types. I stayed (as you definitely should!) for the details I did not know about a hiring spat involving UC San Diego from the early 1990s. Get a load of this.

This is the behavior of someone tacitly acknowledging that what he offers was in less demand and does not want to operate on market conditions. It’s the confession of a professor whose PhD products were becoming uncompetitive in a changing job market that became more interested in signals than noise. It’s tough to read those letters from Mearsheimer and Walt and feel anything but an intense level of second-hand embarrassment for these two in sending it. Departments were increasingly swiping left and it bothered these people enough to do this. This was an era before widespread internet use, but this is, spiritually, identical to “whatever you’re ugly anyway.” Rejection fed derision. I don’t know if either sender wore a fedora in front of their typewriter.

It’s not that these people lost a platform. They still had outlets to, again, complain about scientific modeling and their name still carries enough wait to repeat their basic complaints in outlets like European Journal of International Relations or Perspectives on Politics. There are also Foreign Affairs and Foreign Policy too, which are a bit more geared for the general public than academic readers. Even if you humor the notion that they were being “deplatformed” (to use that language), it’s more the case that their energies shifted to arguably bigger (and certainly more lucrative) venues that were more content with content for content’s sake. Cable news or various periodicals/newspapers won’t demand answers the same way International Studies Quarterly or International Organization would. It’s incidentally a bigger stage too. It’s difficult to be sympathetic at all with these complaints under these circumstances. If Stephen A. Smith left ESPN, he’d still have a platform somewhere (Skip Bayless still does!). However, the troll would still complain, much like a troll like Megyn Kelly complains about being “canceled” by NBC on a new platform on SiriusXM. Perhaps the new platform requires even less effort, but the bottom line isn’t adversely affected. God forbid we be “rigorous” though in saying what we mean, meaning what we say, and bringing evidence to support the claims we want to make.

Yes, that was a clumsy pivot to another instance that is not as widely known, but it’s troll-like behavior emerged in a symposium that was required reading or me in graduate school. This was, for lack of a better term, the “rigor” debate in International Security 1999. It was introduced by Stephen Walt and the subsequent symposium later that year is a sight to behold if you know how to read between the lines. To summarize, Walt was complaining that the discipline’s move toward theoretical clarity (i.e. actually being clear in your assumptions and what you’re arguing) was cramping his style. Here is the official complaint, on p. 8:

My argument is straightforward. The central aim of social science is to develop knowledge that is relevant to understanding important social problems. Among other things, this task requires theories that are precise, logically consistent, original, and empirically valid. Formal techniques facilitate the construction of precise and deductively sound arguments, but recent efforts in security studies have generated comparatively few new hypotheses and have for the most part not been tested in a careful and systematic way. The growing technical complexity of recent formal work has not been matched by a corresponding increase in insight, and as a result, recent formal work has relatively little to say about contemporary security issues.

It’s tough for me to take the “allies balance against threat” guy seriously when he follows that with this tasty lick on p. 13.10 Emphasis added.

These criteria provide a set of hurdles that any social science approach must try to overcome. Although all three are important, the latter two criteria—originality and empirical validity—are especially prized. A consistent, precise yet trivial argument is of less value than a bold new conjecture that helps us understand some important real-world problem, even if certain ambiguities and tensions remain. Similarly, a logically consistent but empirically false theory is of little value, whereas a roughly accurate but somewhat imprecise theory may be extremely useful even though it is still subject to further refinement.

Translation, a la Stephen A. Smith: “I’d rather just talk about how the Cowboys suck than to explain why they do.”

There’s also this one on the folk theorem (pp. 18-19).

Another reason why logical consistency is not enough is the well-known problem of ”multiple equilibria.” Over the past three decades, game theorists have devised ways to build more realistic models by relaxing certain key assumptions (such as the belief that the players have full information). Unfortunately, these more complicated games often contain several equilibrium solutions (i.e., solutions a rational actor would not depart from unilaterally), which means that logical deduction alone cannot tell you which outcome is going to occur. This problem is compounded by the so-called folk theorem, which says that in repeated games with incomplete information and an appropriate discount for the future payoffs, there are always multiple Nash equilibria. Although it is sometimes possible to identify which equilibria will be preferred—Schelling’s famous discussion of ”focal points” was an important effort in this area—”formal mathematical game theory has said little or nothing about where these expectations come from.”

The lay reader may not have raised the kind of quizzical eyebrow I raised reading this, but here’s a way of contextualizing this from my perspective. I tell students “simple is good; simplistic is bad.” All modeling is an exercise in simplification, taking a complex social “object” (e.g. “war”, “state”, “democracy”) and reducing it to essential components that get at the core of the thing in question. It’s why I make allusions to maps or model airplanes as metaphors for what we do and what we want students to think about doing. We can make things more complex and potentially risk generalizability, but I assure you that placing heretofore unmodeled multiple equilibria selection at the core of a process is not that complex. What Walt wants instead is not simplification, but gross simplification. I like the “luddite” metaphor that Niou and Ordeshook (1999) use in response to this. Walt yearns for simpler days of yesteryear where we could be comfortable not thinking about hard stuff or details. It’s just as incurious as an appeal to Rousseau.

I read the full symposium in response to this when I was in graduate school and would encourage you to do as well if you have not already. Bueno de Mesquita and Morrow (1999) largely take Walt (1999) to task for misreading what he cites and for being alarmingly uninterested in 1) the implications of these contributions and 2) making consistent arguments. Martin (1999) repeats much of the same, adds the observation that people like Walt (1999) aren’t being “canceled” (in modern lingo), while also digging into how eager Walt (1999) seems to say “we already knew that” in response to efforts to clarify or move beyond what counted as classic security studies 40 years before the article. Zagare (1999) notes the whole of Walt (1999) is an unstructured mess where nothing follows whatever point Walt wants to communicate.11 Powell (1999), who always did great/challenging work for the -ism field, clarifies how valuable the formal modeling stuff is and offers the pithy complaint that Walt got 44 pages for his screed while every other author in the symposium got ten.

But I want to conclude with Niou and Ordeshook (1999), as I think their “luddite” metaphor is more a four-letter word than seven-letter word when you spell it out. Consider how they close their retort in this (truncated) passage spanning pages 94-96.

The study of politics is, as we argue elsewhere, a field more akin to engineering than to science. Of necessity, our discipline must deal with phenomena that are both too complex for simple, closed-form analysis and too complex for the imprecision of other approaches. This, perhaps, is the attractiveness of imprecision and journalistic discourse-it gives the impression of understanding without revealing the inherent inadequacies of our ideas.

[…]

Finally, we are puzzled most of all by Walt’s assertion that “formal rational choice theorists have been largely absent from the major international security debates of the past decade (such as the nature of the post-Cold War world; the character, causes, and strength of the democratic peace; the potential contribution of security institutions; the causes of ethnic conflict; the future role of nuclear weapons; or the impact of ideas and culture on strategy and conflict)” (p. 46). Even if we were to agree with this statement, we would add that the contributions of Walt’s “other approaches” to this list of security issues escape us as well. But the list is revealing, for it is the product of someone concerned not with science and empirical regularity as those terms need to be understood for the development of cumulative knowledge, but instead with the commentary and informal discussion we find in newspapers and popular journals that has too long appeared under the label “political science.” Such discussion and commentary may be entertaining and even sometimes enlightening, but it remains mere journalism until it can be given the solid scientific grounding that formal theorists pursue.

The references to “newspapers” and “journalism” is thinly veiled if you know how to read between the lines. You know that Stephen A. Smith would still call himself a “journalist” too. There might be a bit of a hubris in the political scientist that dismisses the endeavors of journalism as 100% description and 0% explanation. That may not be 100% warranted, but it feels like it’s at least 99% warranted in the American context when even “description” is a charitable euphemism for what transpires. The Trump-covering stenographer“journalist”, the flamboyant ESPN personality, and Stephen Walt aren’t explaining anything. Not a damned thing. It’s even more frustrating when we care deeply about the thing in question. But they are certainly talking about it. Any yahoo with a keyboard or some other type of creative outlet can do that, though.

I know I’m writing this mostly for me, but it’s a point I want to impress upon students (even if my illustration is very niche). The questions we’re asking about the world around us are far more important than the Dallas Cowboys, which makes the demand for explanation infinitely greater and more important than the demand for conjecture. I want explanations. Be wary of those who only offer the ability to talk about it. I’m not saying explanations are easy, but I am saying they are at a greater premium than whatever a booking agent would quote you for a speaker fee. Try to answer the question; don’t beg it.

-

Notice I said nothing about the merits of Mike McCarthy as play-caller. Cowboy fans seemed to love complaining about Mike McCarthy as a play-caller and how uninspiring his route tree was for his wide receiver corp. In the case above, my eyes typically gravitate toward the caliber of the offensive (and defensive) line. It’s not lost on me that the Cowboys were at their most recent best when their offensive line consisted of all-pros like Travis Frederick, Zack Martin, and Tyron Smith. I’m deliberately downplaying “play-calling” (which is often a generic complaint when specific things aren’t working) and perhaps the caliber of the wide receivers because my perspective places considerable emphasis on play in the trenches. I’ll also confess that the finer points of route trees and coverage shells are beyond my comprehension. Urban Meyer once said “If you want to have a bad team, have a bad defensive line.” I love the sentiment from an offense-oriented coach, but I politely disagree. I think it’s the offensive line. That’s at least my perspective, but I’ll defer to Meyer because he knows more than me. Notice, though, I’m being upfront about my perspective and am acknowledging its limitations. That translates to international relations scholarship. See also the fourth bullet point here. ↩

-

There is very real Stephen A. Smith energy in that passage. In the second clip in the video above, Smith summarizes some plight of the Dallas Cowboys by saying “What can go wrong, will go wrong. It’s just who the Cowboys are.” Again, maybe it’s entertaining, but it sure as shit isn’t informative and doesn’t explain anything. ↩

-

For those of us who have worked on territorial conflict, the realist dismissal of knowing any particular war and why it happened (i.e. “without explaining any given war”) is particularly infuriating. Every war might as well be World War 1. “Geopolitics” (a term I’ve always found weird) kind of nudged us to think about this stuff and it predates Kenneth Waltz getting his dissertation at Columbia. Lewis Fry Richardson had already been working on this topic as we might know it now. I think Statistics of Deadly Quarrels was published posthumously, but he had stuff in print precededing Waltz’s statement. The Correlates of War project would be about 15 years away from producing the data and more general statements that might provide better context to what Richardson was doing. Perhaps finding it intellectually incurious is strong language on my part, but it’s hard not to feel that way as a graduate student after reading Diehl (1992). Gate-keeper effects are strong in this profession and are often unstated. Keep this footnote in mind for when I reference the 2015 Will Moore post. ↩

-

However, it is still imperative to understand that what we know about a war will importantly hinge on whether all, some, or none of the participants are states. Don’t pool types of war together. Please don’t. ↩

-

This passage is inspired/derived from an email to a student on this exact topic. It’s interesting that Waltz criticizes the ambiguity of “polarity” and its multiple definitions in this book when he’s comparably evasive about what he means by it. This is a long-running complaint of mine that we don’t appreciate Wagner (1993) enough. We have no firm definition of what was “bipolarity” and why it should have mattered at all for the behavior of states living in it. We variously define it as a system of just two states (which is wrong and has never existed), a system of two hostile blocs (which begs the question about the behavior we want to explain), and a system where two states basically guaranteed their own survival from other states (which does not imply a hypothesis of the rivalry that they had and why they cared about each other at all). This will matter a great deal for hypotheses about what “tends to form” irregarding what “may or may not accord with the intentions” of states (again, whatever that means). If we don’t know what it was, why should we believe any behavior followed from it? I don’t think Bruce Bueno de Mesquita published this 1999 ISA conference paper in anything other than his textbooks, but notice that bipolarity (whatever that was) led to peace through certainty. So the story goes. That works if and only if power were equal in a system of two units. Not “balanced”. Equal. The moment we relax that and note it was balanced “enough” is the moment we betray a hypothesis about what “tends to form.” Suddenly, imbalances “tend to form” and now it may have led to the “long peace” through uncertainty. I can’t falsify this fucking hypothesis. Isn’t that a problem, according to Waltz (1979, chp. 1)? It would be if you wanted to explain something. It wouldn’t be if you were content to just talk about it. ↩

-

If my academic website had a 1990s splash page followed by a Photoshop job of me cosplaying Niccolo Machiavelli, you would not take me seriously. You would deride me for this obviously clownish behavior. Why is he any different? Why does he get a pass for this conceit? Lots of people say they’ve read The Prince, but has anyone who has said that asked themselves why Machiavelli wrote it and what he might have been trying to accomplish? Are you asking me to believe in the sincerity of the messenger under these circumstances? Do you? Come on, guys… ↩

-

I will never pass up an opportunity to note that Tragedy of Great Power Politics was given a front-cover endorsement by Samuel Huntington, who at the time was in between making an evidently ridiculous argument with a dog whistle and an even more ridiculous argument with a foghorn. “Game recognize game” is a roundabout way of putting it… ↩

-

I attribute this sentence to an undergraduate class I took with Alexander Wendt at The Ohio State University, which I think was the first undergraduate class he taught after moving there. What follows in this paragraph is mostly inspired by Wagner (2007). You should all read Wagner (2007). ↩

-

You can conjure the hypothetical MAGA red hat on the way to the voting booth in November being visited by Christmas ghosts, or blinded by the Almighty, to change their intended vote. The probability of such a late reckoning emerging as an accumulation of the inherent contradictions that underpin this devotion the leader is asymptote to 0. But it’s not 0. ↩

-

Walt (1985) is 40 pages of a closed circle. “Threat” = “perceived intentions.” I perceived an “intention”, and now it’s a threat, and it’s totally a system-level variable and not a domestic factor. Got it. “Power -> threat”, but don’t call it “balance of power”. Call it “balance of threat”. Also got it. I will leave aside the important point that alliances are more than just something like the “all the homies hate Germany” Franco-Russian alliance. Alliances are vehicles to coordinate mutual foreign policy. Russia, for example, routinely uses them as a form of bilateral relationship management and not threat-balancing, per se. Alliances might also be a means to settle pressing foreign policy questions that allies themselves have. These can be the familiar entente (like the one the Brits and French signed after the Fashoda crisis). They could also be the document to outright transfer territory or settle a dispute over it. Alliances are a classically “realist” topic, but the realist treatment of alliances is quite simplistic. ↩

-

A realist offering an argument with a conclusion that does not logically follow the premises. Hey, that only happens all the time… ↩

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.