How to Do a Literature Review

Updated: January 17, 2017, PDF version: here

Any class that requires an essay or term paper at the end of the semester assumes the student will conduct a review of the literature. Professors want to know that the student has engaged in the material discussed through the semester and can advance an original argument on important topics discussed in class. In short, original research requires a review of past research to frame and support the project the student is undertaking.

How to review literature may not be obvious to students. Professors take it for granted in their own research projects because they have years of expertise and a wealth of information. Graduate students have greater difficulty doing a literature review well. The material is well-reviewed by graduate students even if the literature review that follows may not be well-assembled. Undergraduates have the greatest difficulty of all. After all, professors are experts and graduate students have intermediate training. Undergraduates are novices who need the most guidance.

This guide will be tailored toward undergraduate students, though first-year or second-year graduate students may find it useful. I will write it as if I were communicating with a student working on an in-class paper due at the end of the semester.

Looking for Sources

The greatest difficulty for undergraduate students may be not knowing how or where to start. This is understandable since undergraduates are novices in the discipline. Here, I give advice on where to look for sources.

The Syllabus

The most obvious place to start should be the syllabus. For example, a professor of judicial politics who asks students to write an original paper at the end of the semester writes a syllabus that includes readings designed to introduce students to the study of judicial politics. The readings on the syllabus ideally address a variety of scholarship within a particular topic and introduce students to scholarly debates ongoing in the subdiscipline. Students who are unfamiliar with how to start reviewing literature should start with the literature introduced on the syllabus.1 These constitute what the professor believes to be the most important scholarly works on the topic being studied. It should also be interpreted as a signal regarding what the professor expects the student will address in the end-of-the-semester paper, for which the literature review is an important component.

Using Google to Search for Scholarly Sources

The second most obvious thing to do is to “Google it”. One particular Google tool—Google Scholar—will be valuable for every research paper a student writes at any level of education.

Upon arriving at Google Scholar, click “Settings”. Thereafter, click “Library links” on the left column. Here, the student can use Google to access your university’s library. Enter your university’s name (e.g. Clemson), check relevant boxes, and press “Save”. This will allow Google to search for sources, retrieve them, and easily direct the student to the university’s library to log-in and download these sources (i.e. journal articles) as PDFs.

Now, the student can use Google Scholar to search for scholarly sources. To illustrate this process, I’m going to use an example germane to material I teach. Let’s assume I am writing a paper on why citizens rebel against the government for a class on civil wars. I know from the syllabus that there is a well-traveled argument on the topic of civil wars about the motivations of anti-government rebels. Are rebels primarily motivated by legitimate grievances against the government or are they motivated by opportunities to accumulate wealth? This is the greed vs. grievance debate and my task is to write an original paper that could address parts of this debate.

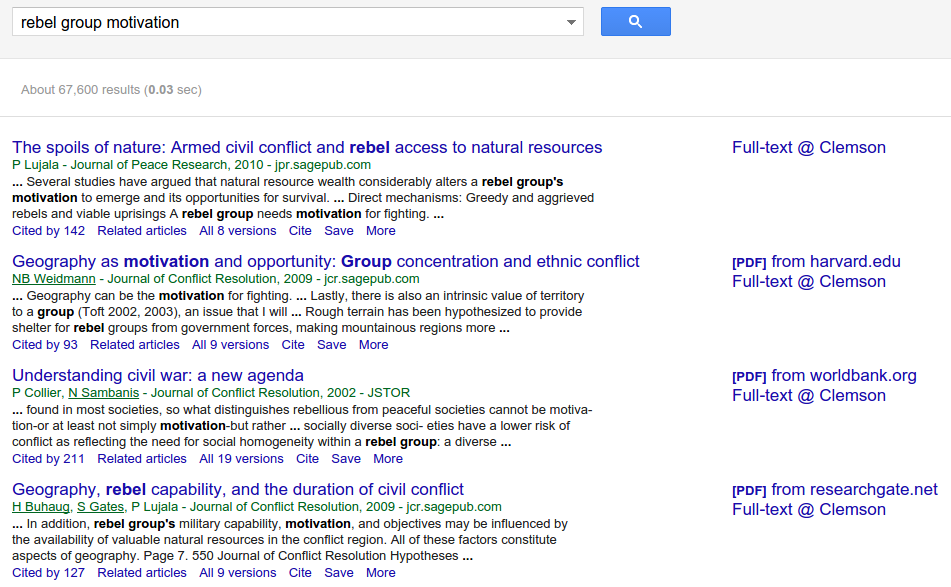

To start my literature review, I go to Google Scholar and enter the terms rebel group motivation. The first page of results returned to me all include well-placed articles on the topic of rebel group motivation that could assist me in my project. Further, every item returned connects me to my university’s library to log-in and retrieve the sources.

What Counts as a “Good Source”?

Professors will judge students on their ability to engage scholarly work on a topic of interest. The student’s particular professor may vary, but I am disinclined to accept a literature review based primarily on newspapers like The New York Times or articles in a magazine like TIME. Political science professors are interested in scholarship, not journalism or advocacy.

Books are great sources. However, different subdisciplines in political science treat books differently. For example, political theory seems to be a more book-driven field from my perspective, though this could be changing. International relations is a more article-driven field. In fact, most conflict scholarship is first published as one or multiple articles before being updated and revised for a book at a later date. Books are great sources, but probably should not be the exclusive source type consulted in a literature review.

There is a general norm in our discipline that the quality of the book is correlated with the marquee name of the university press publishing the book. For example, Cambridge University Press, Harvard University Press, and Oxford University Press are typically considered the best book publishers in political science. Chicago, Cornell, Michigan, Princeton, Stanford, and Yale are great as well. Not all book publishers are university presses. Several commercial publishers like CQ Press, CRC Press, Longman, Norton, Pearson, Prentice Hall, Rowman and Littlefield, Routledge, Sage, Springer, and Wiley also publish quality books. The student’s experience may vary, but most books cited should come from a prominent publisher like those mentioned here. If the student is unsure of the quality of the book, s/he may want to consider searching for it on Google Scholar and seeing how often the book has been cited. Books cited a lot are books that have generated scholarly attention.

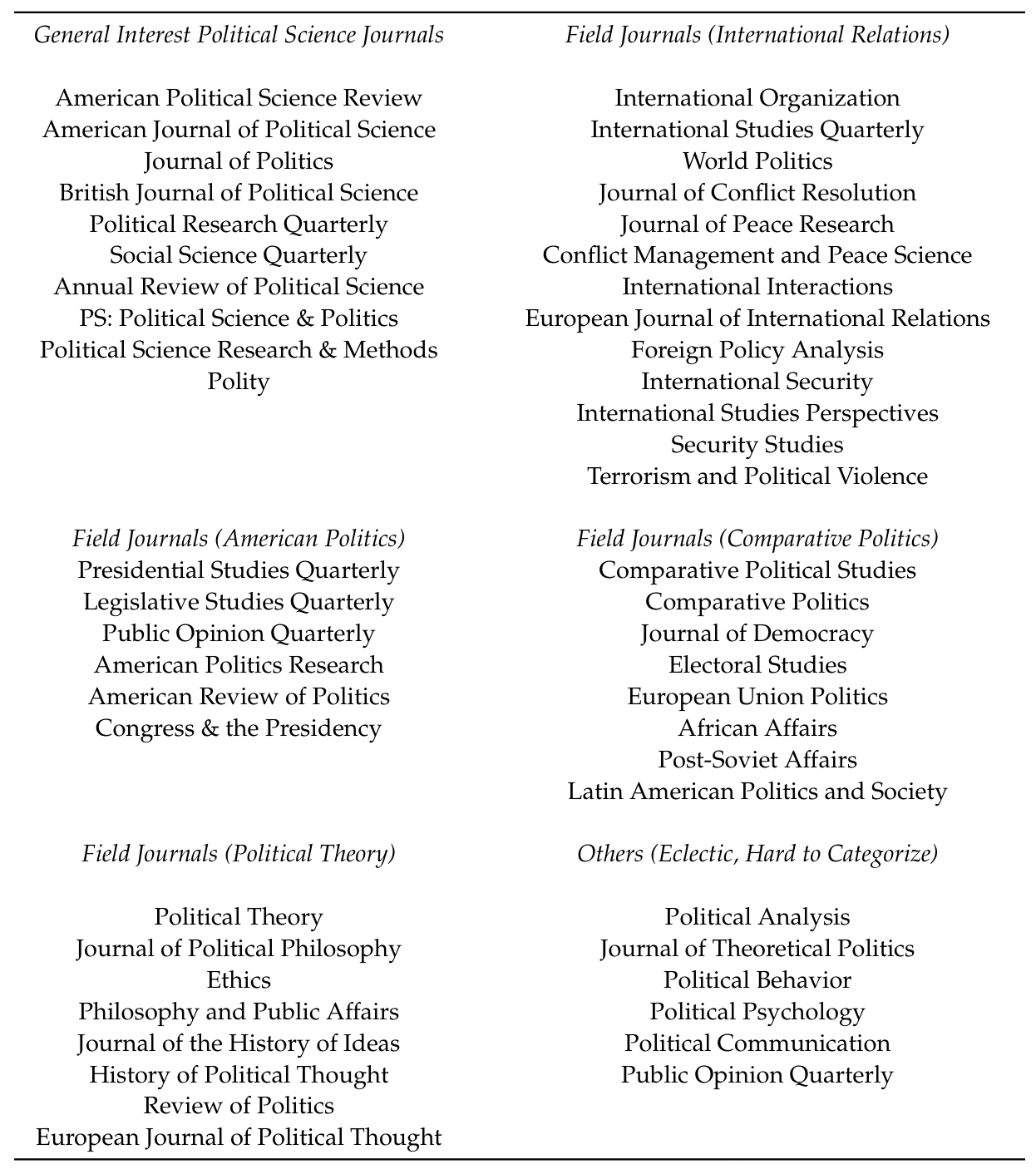

There are a lot of journals in political science that publish scholarship on topics students will research for their end-of-the-semester papers. Several journals are what I would call “general interest”. These journals publish top scholarship of all kinds from all fields. Others are what I call “field journals”, which publish scholarship just within American politics, comparative politics, international relations, or political philosophy/theory. The image constitutes a screenshot of the table I provided in the original PDF that lists journals that professors will expect students to have considered in their review of the literature.2

Gathering Sources Needed for a Literature Review

Whereas graduate students tend to overdo a literature review to demonstrate proficiency with the material, undergraduate students tend to “underdo” it or not do it well. I close this section of the guide with some tips on gathering the right sources needed to write the literature review.

The literature review should be light on sources over 20-years-old. If, for example, the latest citation in a student’s literature review is to something published in 1985, I am led to believe the student did not review the literature well or the student is addressing an argument for which there is no present academic interest. This is not to say that much older sources are worthless. For example, any paper on retrospective voting in the United States will likely include a citation of VO Key’s (1966) seminal study of The Responsible Electorate. However, much more has been done on that topic since Key and should be the heart of the literature review.

Gathering sources for undergraduates may require “a literature review of literature reviews” approach. Find the most recent article on the topic of interest.3 Read the article, but focus on the literature review. Follow the sources being discussed in the literature review. Repeat as necessary until confident that the search of relevant materials has been exhausted.

Writing the Literature Review

Students may find themselves writing all (or pieces of) the literature review while reviewing the literature itself. This guide will assume writing the literature review follows an exhaustive search and evaluation of relevant scholarship to illustrate the process.

First, students should know the purpose of the literature review. The job of this section of a research paper is to provide a summary of the current state of political science scholarship on a topic of interest. It is not a place to demonstrate to the professor that the student read a lot of stuff. It is not an annotated bibliography. It is not a place to just list arguments that are disconnected from any bigger point. The literature review the student writes must justify the student’s study by building on what others have done previously and how the student believes the study to follow will advance scholarship on an important topic. At a minimum, the treatment of previous literature should answer the following questions. What’s the puzzle or the problem? What do we already know? What do we not know? Why is it important?

“Why is A the case and not B?”

This type of literature review, from my vantage point, is common in works of political theory (e.g. “why aren’t there competing ideologies to Locke in the United States?”, The Liberal Tradition in America) and international relations theory (e.g. “why didn’t the United States and Soviet Union fight each other?”, The Long Peace). It does carry a normative tone (or advocacy) if it is not done right. Focus more on what “is” and not what “ought to be”.

“We know a lot about A but we know little about B. However, A suggests B.”

This is what I call the “unaddressed question”, “the next step”, or “gap in the literature” frame. Be careful with this type of literature review. It may be appropriate, given the problem being studied, but a lot of boring or uninteresting questions go unaddressed. Further, political scientists I know tend to cringe at the phrase “filling a gap in the literature”. Emphasize the substantive importance of the problem left unaddressed if this is the route the student goes in the literature review.

“Author A and Author B make different predictions about C. Who is right?”

This is a “competitive hypothesis test” or “horse race” frame. Pit competing explanations against each other or try to synthesize a scholarly disagreement. James Fearon’s (2002) “Selection Effects and Deterrence” in International Interactions is a great example of this type of frame.

The “attack” frame is a derivation of this. A student may believe that Author A’s explanation is incorrect on many levels or fails to explain several important observations. Contingent on the question or the topic, this may be appropriate. Be careful to “critique” and not “attack”. Science is about advancing, even improving, what has been done previously. Be gentle in the approach.

Conclusion

Howard Becker captured the point of the literature review well in his 1986 book, Writing for Social Scientists. Long story short, others have addressed the topic the student is addressing. The student’s job here is to reassemble what others have done with the goal of constructing an original analysis.

Imagine you are doing a woodworking project, perhaps making a table. Fortunately, you needn’t make all the parts yourself. Some are standard sizes and shapes… Some have already been designed and made by other people… All you have to do is fit them into the places you left for them, knowing they were available. You want to make an argument instead of a table. You have created some of the argument yourself, perhaps on the basis of new data or information you have collected. But you needn’t invent the whole thing. Other people have worked on your problems or problems related to it, and have made some of the pieces you need. You just have to fit them in where they belong. Like the woodworker, you leave space, when you make your portion of the argument, for the other parts you know you can get. You do that, that is, if you know that they are there to use. And that’s one good reason to know the literature: so that you will know the pieces are available and not waste time doing what has already been done (pp. 141 - 142).

Finally, students can learn how to write a good literature review by reading literature reviews. This should be quite useful for entry-level students who need this guide the most. I am a firm believer that students learn how to write by reading and emulating what they read. Read. Write. Edit. Repeat as necessary.

-

This also assumes the student has read the readings contained on the syllabus. Failing this, the student is running a fool’s errand in writing a paper of which s/he knows nothing. ↩

-

While I believe my list is mostly representative, my expertise is in international relations. My confidence in the representativeness of the field journals for international relations is greater than my confidence in the representativeness the journals in other fields like political theory. ↩

-

One way to find the most recent article is to narrow the temporal domain in Google Scholar to all articles published after 2008 (for example). ↩

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.